GREENE COUNTY HISTORIAN’S BLOG

The Wreck of the Swallow

The story of a calamitous shipwreck on the night of April 7, 1845 in Athens, New York.

On the snowy evening of April 7, 1845 the steamboat SWALLOW departed her dock at Albany loaded with approximately 250 passengers bound overnight for the City of New York. Fashionable and fast, the SWALLOW offered businesspeople and time-conscious travelers one of the fastest and most comfortable conveyances between the capital of New York State and its unofficial business capital at New York City. The evening route was intended to leave passengers rested and ready the next morning to conduct business at their respective destinations. None knew the journey would end a short two hours later in a cataclysm of shattered timbers, fire, and water — a tragedy summoned by a culture of heedless profiteering endemic to the operation of the steamboats of that age.

The SWALLOW was owned jointly by “The People’s Line of Steamboats on the North River” and “The Troy and New York Steamboat Association.” Daily operations were orchestrated by the Association, a profit-minded assembly of investors including approximately one hundred shareholders with a board of five trustees and three directors. Naturally, much of the decision making behind the operation of the SWALLOW emphasized publicity and revenue over passenger safety.

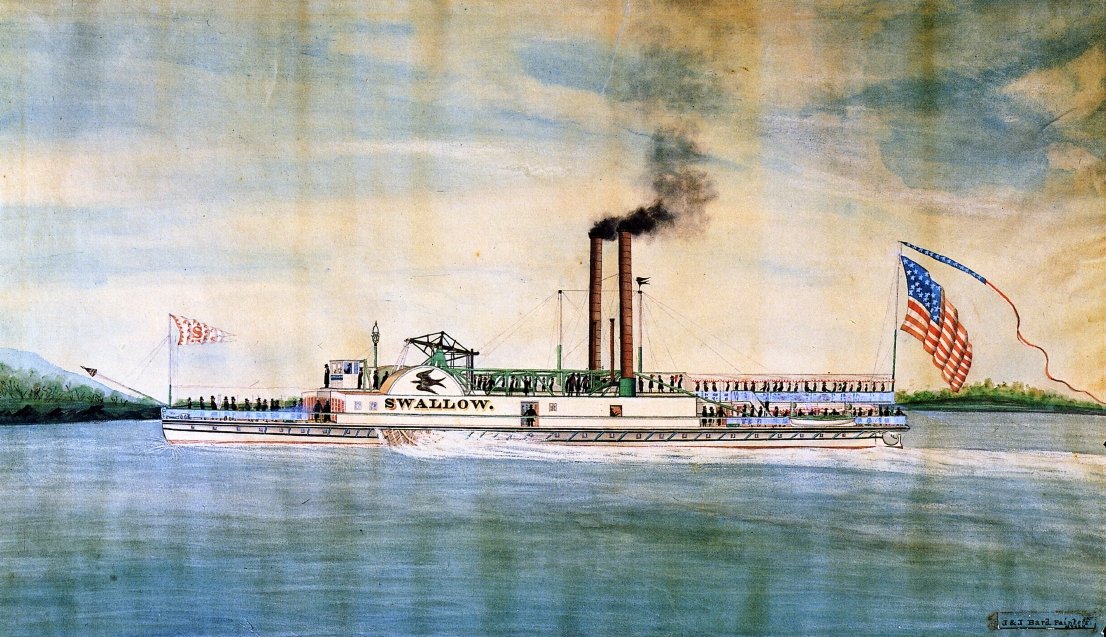

The Steamboat SWALLOW as she appeared around the time of her commissioning as a day boat in 1836. Painting by celebrated maritime artists James Bard (1815-1897) and John Bard (1815-1856), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Swallow_(steamboat_1836)_by_Bard_Bros.jpg

The speed of the SWALLOW, like many of her contemporaries, was an important selling point and a subject of pride among her stakeholders and management. Following a refit at the end of the 1844 season it was held that the SWALLOW could make upwards of seventeen miles per hour as her top speed — quite fast for that time. This was known because she and competitor steamboats frequently undertook unofficial races which jeopardized the safety of boatloads of paying customers in the name of attracting more passengers to a winning boat on a subsequent trip. By the mid-1840s such races were technically illegal, but no system existed to identify and address those who continued the practice.

While winning steamboats certainly made the headlines in regional papers with regularity, so too did news of the alarmingly frequent disasters that befell boats which were pushed too hard. Boiler explosions, fires, groundings, and collisions appeared in the news just as often as headlines concerning triumphs and broken speed records. The potential for disaster was compounded by flaws in the way steamboat officers were selected. As one example of this systemic problem the pilot of the SWALLOW, William Burnett, was previously “addicted to the use of ardent spirits” though he claimed to have had only one beer while on board the vessel that fateful night. This same pilot had run the SWALLOW aground twice in the past and once sank a sloop in a collision. All of this culminated in his previous dismissal from the post for negligence. His subsequent reappointment prior to the disaster illustrates just how flawed the corporate culture was that would place a man in a role they were demonstrably ill suited for.

In the same Senate report that describes pilot Burnett’s previous struggles with alcoholism and sloops appears a scathing indictment of the entire command structure common among Hudson River Steamboats at that time. The Captain, contrary to every obvious principle concerning the management of a ship, did not have clear authority over the Pilot and Engineer, effectively rendering him a figurehead with more responsibility over the management of passengers than the actual navigation and operation of the vessel. Indeed the tradition of Ships Pursers being elevated to the position of Captain among Hudson River Steamboats endured long after the SWALLOW met its end. With no single experienced person clearly in command there was no possibility of sound judgement ruling difficult or dangerous situations. Then again, it shouldn’t have been a grand question as to whether running at speed was a prudent idea on a dark snowy night.

This fatally flawed command structure, paired with a desire among stakeholders and crew alike for speed, had already doomed the SWALLOW as she rushed southward through the night. The SWALLOW rapidly outpaced the ROCHESTER and EXPRESS, fellow night boats which had left Albany at the same time, and likely made an average of fourteen miles per hour the entirety of the distance between Albany and a rocky outcropping called Dooper’s Island along the shoreline at Athens, New York. Around eight in the evening residents of Athens and Hudson alike were woken by a crash heard at least a mile in all directions. Within moments those near the banks of the River in Athens observed the glow of flames that briefly illuminated the silhouette of a steamship, its bow driven over thirty feet into the air upon a rock and quickly sinking by the stern. Passengers poured out onto the decks, many chancing the water to make distance from the wreck lest it continue to burn. The stern sank within five minutes, extinguishing the boilers and nascent fire and plunging all into darkness.

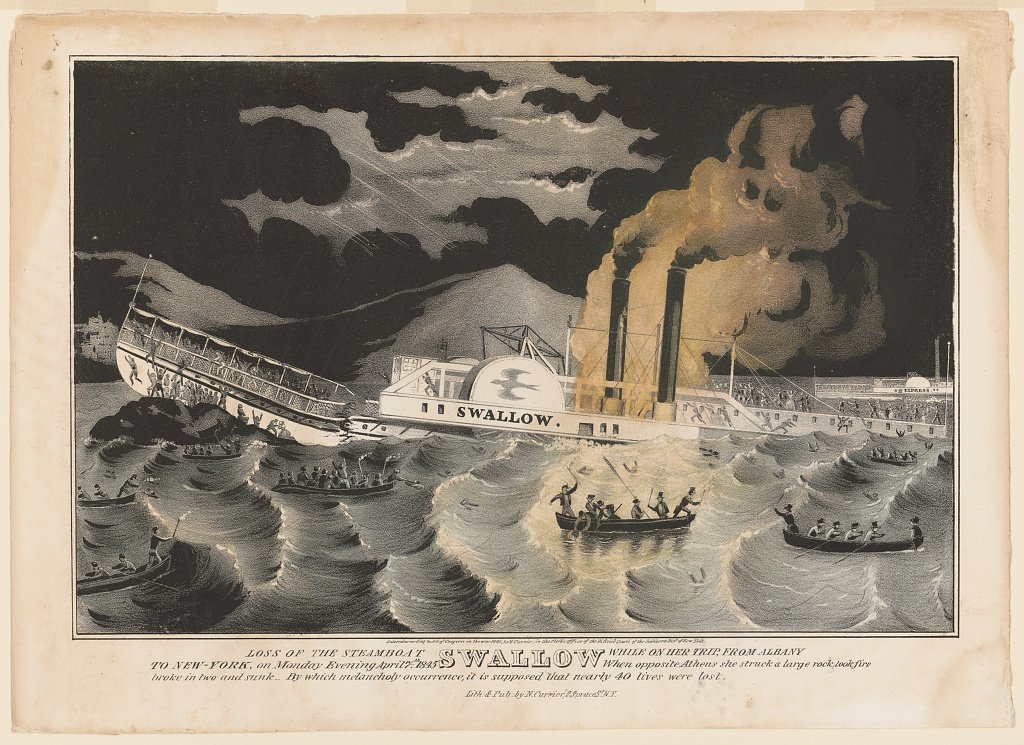

Loss of the steamboat Swallow while on her trip from Albany to New-York, 1845. New York: Published by N. Currier. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002709958/.

Confusion dominated in all quarters from the moment the SWALLOW ran aground and sank. In the common custom of the time no clear accounting of the total number of passengers was ever taken, so it remained (and still remains) uncertain what the exact death toll was. Newspapers throughout the valley began publishing accounts within a day of the sinking, and it was claimed by some that upwards of forty persons died, though only thirteen bodies and one missing child could be identified by the end of the month. The hour of the sinking, the subsequent destruction of the aft staterooms by river currents, and the removal of survivors by the ROCHESTER and EXPRESS as well as good samaritans in Athens meant it was unclear for a time exactly who survived and where they ended up.

Conflicting stories as to the circumstances that precipitated the disaster filled newspapers in the ensuing weeks. These ranged from inclement weather, to racing on the part of the steamboats running that night, and even simple base negligence by the pilot and captain. A select committee charged with investigating the disaster on behalf of the New York State Senate began collecting salient facts within days of the sinking, including detailed measurements of the situation of the wreck and its relationship with the shoreline.

Pilot William Burnett gave testimony certain to cast himself in a prudent light, stating that after coming past Four Mile Point he slowed the SWALLOW to approximately seven miles per hour and proceeded with caution. This testimony conflicted with his additional assertions that he had fine visibility and knew his position relative to the Athens shoreline moments before the collision. Ultimately he blamed a strong crosswind for blowing the SWALLOW off course within about six hundred feet of the rock. The written reply of the select committee, after introducing the pilot’s narrative, read thus:

“The committee cannot reconcile this story with the facts.”

The select committee chalked up Burnett’s testimony as predominantly nonsense, and rightly so. The SWALLOW covered the roughly 27 miles from Albany in two hours. Simple arithmetic gives us an average of almost fourteen miles per hour being necessary to accomplish that. Accounting for the points in the journey when the pilot gave an account of his speed as being half that or less (including the departure from Albany and his oddly prudent pass through the Athens channel) this means the SWALLOW would have had to exceed its top speed elsewhere at other dangerous points in the channel coming south from Albany.

That Burnett’s testimony was riddled with falsehoods is corroborated by several facts uncovered by the select committee. The absurd position of the wreck, which couldn’t have arrived so high upon the rock unless it had been moving at a tremendous rate, illustrated clearly the speed and force of the impact. Some passengers submitted a subsequent resolution defending the pilot’s testimony, but others found fault in it and the question remains whether passengers enjoying the evening in comfortable aft staterooms could have had a clear sense of the Ship’s speed in the dark.

Likewise, the committee found it irregular that any pilot would have decided to slow their vessel at a position where the channel became so clear and defined. It was in fact highly unusual among pilots to slow their speed at Athens and the report elaborates on this point at length. Indeed, even Burnett said he could see his location well despite the weather. Lastly, none except the pilot claimed to have observed any wind that could have acted with such force to cast the SWALLOW off course in such a short distance.

Detail of a map prepared by the select committee showing the position of the wreck in mid-April of 1845.

The SWALLOW came to rest upon the rock more or less at coordinates 42.263750, -73.804724. This location is now part of the shoreline at Athens situated immediately north of the the Village’s sewage treatment plant. Where it had once been known by several names depending on the source, the sinking thereafter earned the island the moniker “Swallow Rock.” The rock endured at least into the 1870s, at which point encroaching fill for an ice house finally covered it up, but local writers were able to refer to the location with certainty into the 20th century.

This is not to say that the sinking of the SWALLOW didn’t endure in collective memory. Generations of Athenians were regaled by tales of the disaster, and debate as to the causes of the wreck have captured the imaginations of countless writers and historians. In a way this was the only lasting result of the tragedy. The wreck of the SWALLOW was removed and hauled away about a month after the sinking - its timbers famously salvaged for a house in Valatie, the running gear repurposed, and its dead buried. William Burnett was put on trial for manslaughter but acquitted, and the night boats kept running as before.

The select committee’s report was submitted to the senate at the end of April while salvage operations were underway at Athens. It conveyed the nascent awareness of a nation becoming increasingly sensitive to the mounting evidence of an industry running roughshod over the best interests of the traveling public. There was undoubtedly some appeal in a slow boat where passengers survived over a fast one which perpetrated the occasional massacre, and it didn’t take men of vision to see that regulation must reign where decency would not.

In calling for new safety regulations, the committee members included in their conclusions a passage from Emer de Vattel’s The Law of Nations: “If a nation is obliged to preserve itself, it is no less obliged carefully to preserve all its members.” It would take almost a decade and two more horrifying accidents on board the HENRY CLAY and the REINDEER (standouts in a slew of more minor incidents) to bring about the regulation necessary to improve the safety of steam transportation on the Hudson River.

By Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian. Questions and comments can be directed to Jon via archivist@gchistory.org

Additional Reading:

Senate Document no. 102 submitted by the Select Committee appointed to investigate the cause and circumstances of the late disaster of the steamboat Swallow, on the Hudson River, April 26, 1845.

Captain William Benson’s relation of the tale of the disaster, courtesy of the Hudson River Maritime Museum.

Andrew Amelinckx’ version of the tale as published on Hudson River Zeitgeist.

The Irish Colleens of Saint Joseph’s Chapel

Debunking the myth of the Irish Colleens of Saint Joseph’s Chapel in Ashland, New York.

Near the Ashland/Prattsville Town Line overlooking the valley of the Batavia Kill stands a small chapel and churchyard on a rise above State Route 23. Passersby generally pay no heed to it as they travel past at sixty miles an hour, but for those who catch the sign “Oldest Catholic Church in the Catskills” and take time to stop the rewards are manifold. Saint Joseph’s chapel claims to have been built around 1800 during the earliest years of the settlement of Old Windham, and one might believe it to see the full churchyard with gravestones edging right up to the building’s walls. One stone in particular stands out — a granite shamrock upon which is carved the following:

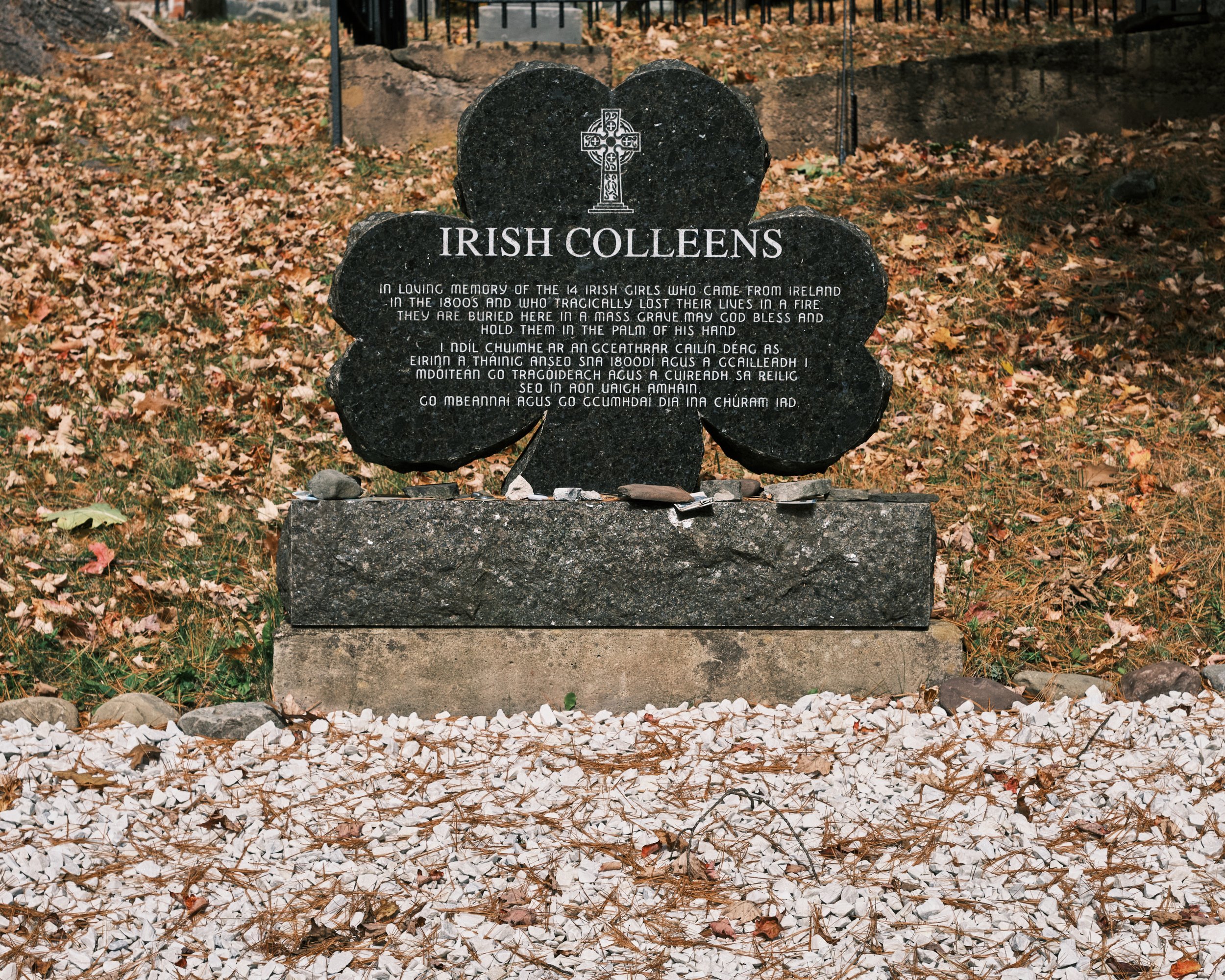

Irish Colleens

In loving memory of the 14 Irish girls who came from Ireland in the 1800s

and who tragically lost their lives in a fire. They are buried here in a mass grave.

May God bless them and hold them in the palm of his hand.

The passage is repeated in Irish directly below. The humbling spectacle of the oldest Catholic Church in the Catskills paired with this marker near its entrance would create a particularly poetic and stirring composition were it not for some inconvenient details… Saint Joseph’s is not the oldest Catholic church in the Catskills, and the tragedy of the fourteen Irish Colleens never happened.

The granite monument to the fourteen Irish Colleens which stands near the entrance to Saint Joseph’s chapel and cemetery in Ashland, New York. Palmer Photo.

The marker to the Irish Colleens of Ashland is responsible for fomenting at least one or two inquiries annually by phone and email to the Greene County Historical Society. The story also invariably gets recycled now and again on social media. Countless people have offered speculation and possible avenues of research to uncover more details about this tragic yet vaguely contextualized disaster, but none have borne fruit and no local historian has ever found a lead. Thus, in order to finally put this myth to bed we must first consider the facts surrounding the industrialization of the Northern Catskills, the development of the Irish immigrant community in Prattsville and Ashland, and the origins of Saint Joseph’s Chapel itself.

The story of the arrival of formal Catholic services in Greene County is tied hand in hand with the creation of the great tanneries of Hunter and Prattsville in the second and third decades of the nineteenth century. William Edwards’ New York Tannery at Hunter village is widely considered to be the great pioneer of that industry and was put in operation in 1817 with backing from investors in New York City. The New York Tannery and others like it created a considerable demand for labor in the tanneries themselves and in adjacent trades. With every tannery that opened so followed a legion of tanners, carpenters, blacksmiths, drovers, bark-peelers, mechanics and the like — all added to the growing tally of skilled and unskilled labor rapidly filling the Northern Catskills.

At Hunter as early as 1830 it is claimed there was a large enough immigrant Irish Catholic contingent among the laborers there to merit the occasional visit of a Priest from Albany, which was then part of the New York Diocese. By 1839 those congregants were so numerous that a subscription was raised to secure funds for the construction of a church. This culminated in the completion of Saint Mary of the Mountain as the first Catholic Church in Greene County with Rev. Bernard O’Farrell as pastor the following Spring. Two years later in 1842, following the appointment of Rev. Michael Gilbride as the second pastor at Saint Mary’s, work was begun to create a mission chapel to service the growing Catholic contingent at Red Falls — a small hamlet east of Prattsville village along the Batavia Kill.

The Metropolitan Catholic Almanac first lists a church at Scienceville (the old name for Ashland) on the directory of Catholic houses of worship in the New York Diocese in 1843. The church at Hunter had been listed previously beginning in 1840, making Saint Mary of the Mountain the oldest Catholic Church in Greene County and Saint Joseph’s Chapel a close second. With the demolition of Saint Mary’s in 2017 the chapel at Ashland can now safely claim oldest surviving Catholic church in the County, though by no stretch of the imagination could it ever be dated to “circa 1800” — eight years before the Diocese of New York was even formed.

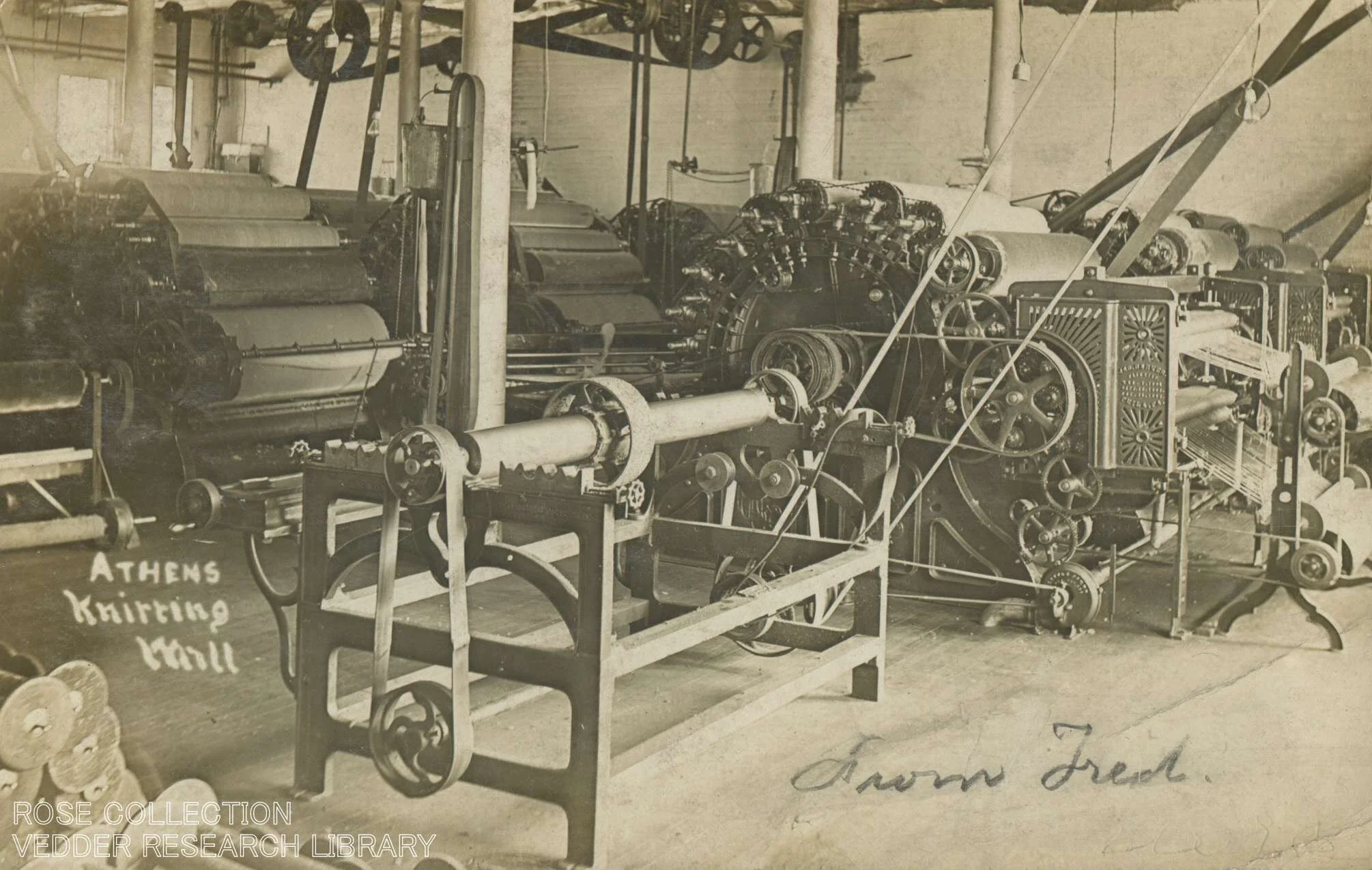

The need for a church at Red Falls was precipitated by the same type of development that had fomented the rise of an Irish Catholic community at Hunter. The vast tannery of Zadock Pratt at Prattsville (established in 1825) and one run by Foster Morss and his son Burton (established in 1830) at Red Falls were catalysts for the development of those communities, but they soon became just one part of the rapidly evolving industrial landscape in that section of the mountains during the Antebellum period. By 1850 Prattsville and the newly formed town of Ashland sported a cotton mill and two hat factories in addition to a number of lumber and grist mills, a developing cottage dairy industry, and the old established forest industries.

It should be said before we continue that the most important piece of evidence that the Irish Colleens tragedy never occurred is the fact that it was never recorded, reported, or recollected by anyone in the time since the event could have transpired. Fourteen women dying in a fire would be the second greatest disaster behind the Twilight Inn fire to have ever occurred in the County’s history, not to mention being the greatest industrial disaster to ever occur here. Such things do not get omitted from collective memory, nor were such stories overlooked by newspapers.

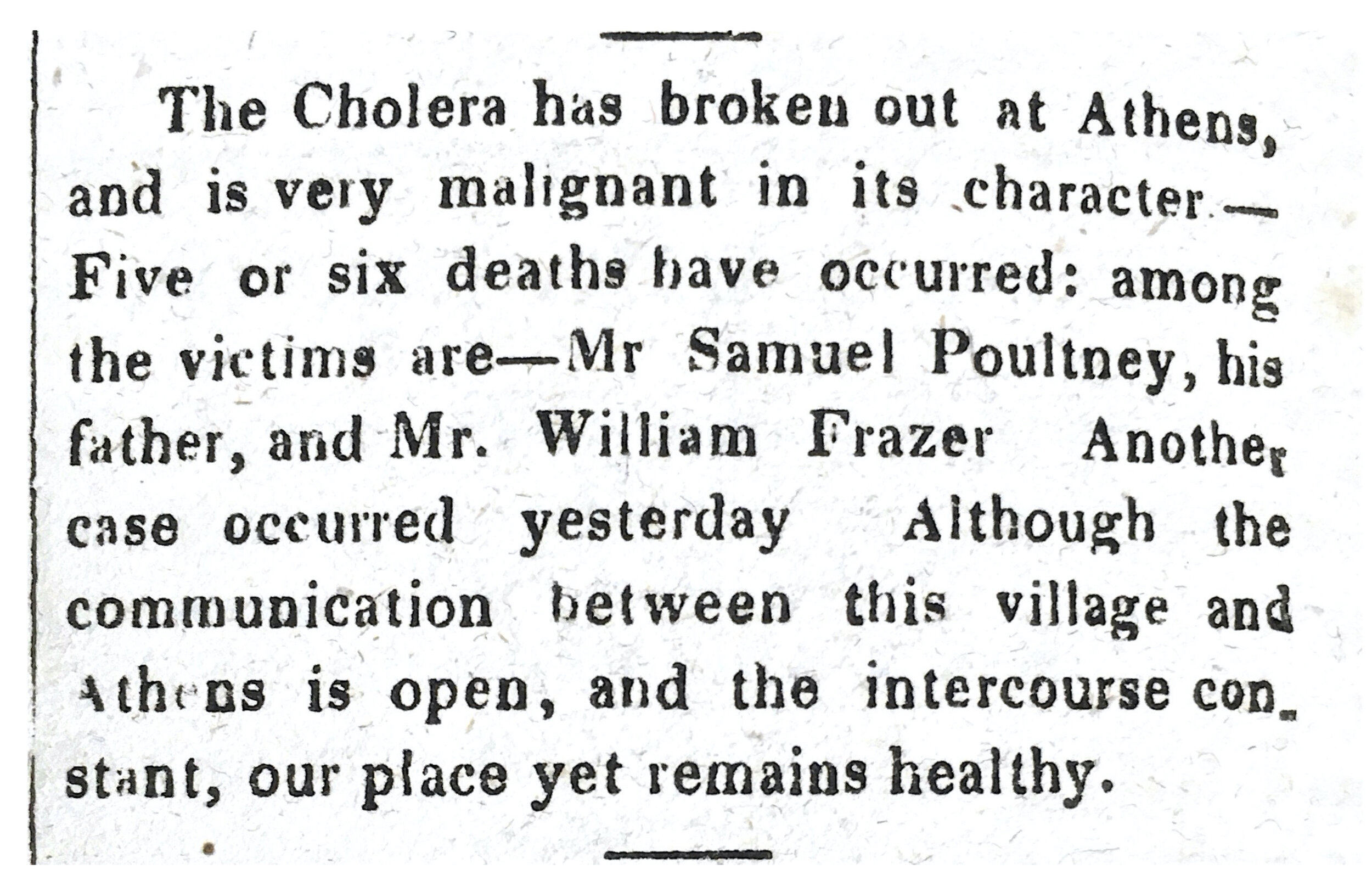

Disasters such as the one alluded to by the Irish Colleens monument were the catnip of newspaper editors in the 19th century. Editors reported every disaster to befall their respective communities - be it housewives catching fire while tending the stove, children drowning, uninsured warehouses burning down, or people dying of hydrophobia - and if such disasters weren’t befalling their readership then editors simply copied disaster news from other papers around the country. The reason for this was of course because at the end of the day disasters sold papers. People would have gobbled up the tale of fourteen immolated Irish women in the Catskills. No such disaster can be located in any newspaper database, and no mill or tannery in that area ever burned with the loss of any woman’s life.

It is important in supplement to this glaring lack of evidence to establish whether a scenario ever could have existed in which fourteen Irish immigrant women could have been killed in a fire - be it in a mill, boarding house, or otherwise. This analysis begins with the 1850 United States Census, being the census immediately following the height of the Potato Famine (when the Irish immigrant population should have been proportionately high) and subsequent to the 1848 opening of Burton Morss’ cotton mill at Red Falls. The 1850 Census is also the first in which every member of a household is listed with their place of birth.

What that census illustrates broadly is the following: a little over 6% of the population of Prattsville claimed to be Irish immigrants (≈125 persons out of 1,989 people), while a little over 2% of Ashland’s population (≈29 of 1,290 people) listed Ireland as their place of birth. Of those people, the Irish immigrants were predominantly members of family groups in which one or both of the parents were immigrants whose children were mostly or exclusively born in the United States. Irish immigrants not living in a family setting were predominantly unattached men working in industry or household servants and boarders generally numbering no more than one or two persons in the homes of established local families. One home in Ashland contained six immigrant Irish men with no clear trade specified living with Solomon Christian, a local farmer with a young family.

The entry from page 18 of the enumeration of Ashland, Greene County, from the 1850 United States Census showing Solomon Christian, his young family, and a slew of boarders who were predominantly male Irish immigrants.

The 1855 New York State census illustrates some interesting changes. Roughly 5.2% of Prattsville’s population reported their birthplace as Ireland (≈84 of 1588), while just under 2% of Ashland does the same (≈20 of 1094). This decrease, particularly in the Town of Prattsville, may have been due to the closure of some local tanneries and the transformation of the economic landscape of the town. Broadly the same fact remains constant however that most Irish immigrants lived within family units or were otherwise unattached males living as boarders. Several more unattached young women or daughters of families living elsewhere in town are listed working as servants with established local families.

The 1855 census interestingly also lists a Roman Catholic church at Ashland with an attendance of about 150 congregants — this number is roughly equivalent to the total number of Irish-American families living between Prattsville and Ashland who could have been potential congregants. This assumes for example that the fifty or so children appearing in households where at least one parent was an Irish immigrant in Prattsville would make up a portion of those attending while also not accounting for those practicing Catholicism who were not Irish-American.

The next census examined was the 1865 New York State Census following the Civil War. In this census surprisingly only 2% of the population of Prattsville reported their birthplace as Ireland, and in Ashland eight people stated they were Irish immigrants. These decreases correspond with a continuing decrease in the total populations of each town. Notably the Roman Catholic church is not listed as an active congregation at this time, though it reappears in later censuses. As with previous years those born in Ireland are almost exclusively part of family groups or servants in households of established local families.

The 1870 United States Census, 1875 New York Census, and 1880 United States Census all continue to illustrate this trend of general decline in percentages of the population of Prattsville and Ashland who reported their birthplace as Ireland. By 1880 nobody reports their birthplace as Ireland in either town. Though this may reflect minor reporting or recording biases it nonetheless illustrates how rapidly the initial Irish-American community associated with Saint Joseph’s appears and then disappears.

Cumulatively, these censuses illustrate that it would have been highly irregular in the years following the organization of Saint Joseph’s Chapel for fourteen immigrant Irish women to have found themselves in a scenario where they all could have died in a fire. While an event at a workplace would certainly be most likely, any fire that could have occurred would have killed more people than exclusively Irish immigrants. Take for example Burton Morss’ cotton mill, which was the largest employer at Red Falls, with a claimed figure of forty women and thirty men employed while it operated between 1848 and 1881. It is evident from the 1850, 1855, and 1865 censuses that the mill employed both men and women, and that many people from established local families worked alongside those who had been born elsewhere. Likewise, boarding houses in the area seemed to have catered to both men and women and boarders didn’t hail exclusively from one region or place of birth.

❈ ❈ ❈

While this is all quite interesting it should come as no surprise that all evidence stands in contrast to the tale related on the Irish Colleens monument. In fact the only surprise here seems to be the monument itself, which so far as can be discerned appeared along the staircase to the chapel sometime in the 1990s. An inquiry submitted by a researcher to the Greene County Historical Society in 2009 notes the appearance of the marker “about ten or fifteen years ago” and relates his desire to confirm the circumstances it commemorates. The marker pairs odd specifics (fourteen women) with useless dates (“the 1800s”) and omits where the disaster happened, only that there was a fire. Frankly the monument reads more like the end result of a children’s game of telephone… and that analogy may not be far from the truth of its origins.

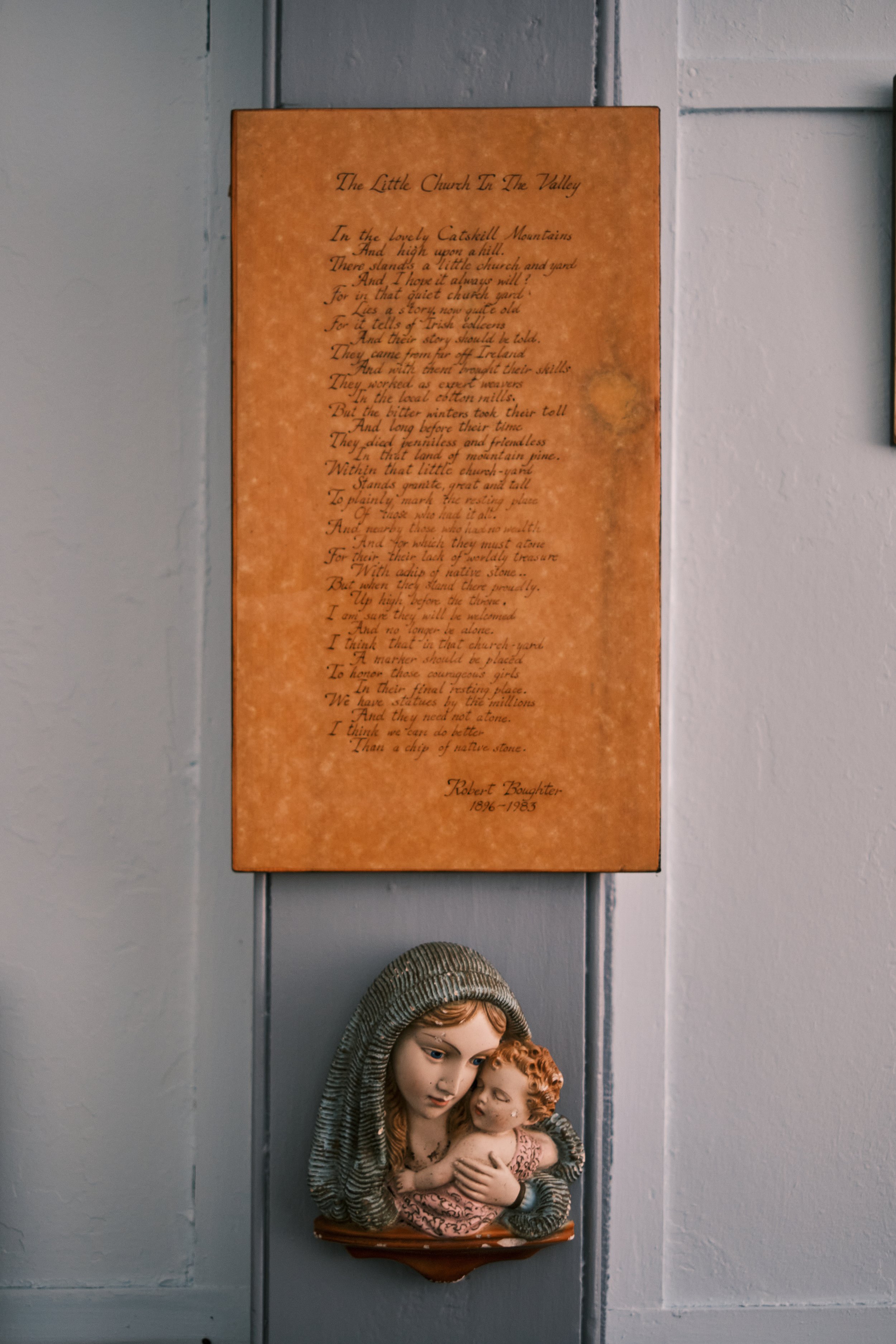

Robert Boughter’s poem “The Little Church in the Valley” displayed within Saint Joseph’s Chapel.

At some point probably in the 1950s or 1960s a poem was written by Robert Boughter of Windham lamenting the “haves and have nots” tale of the Irish immigrants who came to work in the mountains in the nineteenth century. His poem to the memory of the Irish Colleens, while not exemplary of the form, is a poignant and earnest tribute to the story Boughter understood to be the truth about the people who came to work in Red Falls at Burton Morss’ cotton mill. He paints a vision of the classic New England textile mill wherein floor upon floor of immigrant women and girls from the countryside toiled away in despair on behalf of fat cat bosses.

In Boughter’s poem those women die in anonymity after having lived a life of anonymity, being buried as he puts it “beneath chips of native stone” while nearby “stands granite great and tall to plainly mark the resting place of those who had it all.” He closes with an admonition to the reader that a marker should also be placed to commemorate those women, not alluding however to any disaster or mass grave. Boughter simply laments the tragedy of the scores of uninscribed fieldstones marking their burials, assuming without evidence that many represented the unattached “Irish Colleens” with neither family nor means to adorn their own graves. The mountains are loaded with cemeteries containing scores of unmarked headstones made from native fieldstone slabs, and it will take considerable further study to determine if this phenomenon is socioeconomic, an expression of piety, or some mixture of the two. Either way it was not a phenomenon unique to Saint Joseph’s or the Irish Catholic community in Red Falls.

Some of Robert Boughter’s aptly styled “chips of native stone” in the Catholic cemetery at Saint Joseph’s Chapel.

Boughter is of course imposing his own expectations on what the nature of the working community at Red Falls was during the mid-19th century and assuming that primarily imported labor comprised Burton Morss’ workforce. As said previously the censuses of 1850, 1855, and 1865 plainly illustrate this was not the case. Were Boughter’s vision of the past correct, this would have required nearly fifty percent of the Irish immigrant community in Ashland and Prattsville at its peak circa 1850 (roughly 150 people total) to be employed just at Morss’ mill, never mind all the other places those people listed as their actual occupations. Moreover, the cotton mill operated until 1881, well after the population reporting their birthplace as Ireland in both towns had dwindled to virtually zero. This all aside, it is important to remind everyone again that none of the mills there ever burned with catastrophic loss of life.

When Boughter died in 1983 he was laid to rest in the back of the cemetery at Saint Joseph’s among the “chips of native stone” he fancied as being the markers of the Irish Colleens. On his grave he had inscribed “The Irish Colleens” followed by his own epitaph “In Memory of Robert Boughter, 1896-1983.” In this way his own grave finally fulfilled the need he perceived for a marker to honor the women central to the story he contrived of the mill at Red Falls. This makes the subsequent appearance of the Irish Colleens monument not only somewhat redundant, but also illustrative of a progression in the evolution of an already somewhat imaginative vision of the past. Thus the Irish Colleens monument stands today an expression of misconstrued recollection rather than a long-overdue tribute to an actual tragedy.

History of course is merely our conversation with the available facts of the past. The discovery of new details can move that conversation in many directions, but the conversation only bears fruit if we act in concert with the evidence at hand. Perhaps it is time — out of respect to the legitimate story of the Irish Catholic community that once called this corner of the Catskills home — to finally put this legend to rest.

By Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian. Email Jon at archivist@gchistory.org

The interior of Saint Joseph’s Chapel, Ashland, New York. Palmer Photo.

On The Frontier

A map sheds new light on the life of Johannes Strope, a settler who was massacred in Round Top, Cairo, NY in 1780.

This article originally appeared online under the title “William Cockburn’s Map of the McLean, Treat, and McLean Patent.”

In a recent two-part article for Porcupine Soup, Sylvia Hasenkopf shed light on the grim story of the 1780 Strope Massacre in the hamlet of Round Top in the Town of Cairo. The circumstances of this raid by warring Indians and the killing of Johannes Strope and his wife were recorded by regional author and pamphleteer Josiah Priest and sampled heavily by Charles Rockwell in his book The Catskill Mountains and the Region Around. Beyond the circumstances of the massacre narrative little today endures to relate the substance and nature of Johannes Strope and his family’s life on what was then one of the frontiers of European settlement. A recently cataloged map helps dispel a bit of this obscurity.

William Cockburn was a native of Scotland with an artist’s eye and a knack for numbers. He probably emigrated to the Province of New York sometime in the early 1760s, and by the end of that decade was engaged virtually full-time surveying and delineating the vast collage of (often inconveniently overlapping) land patents which for almost a century had slowly crept their way westward from the Hudson to the interiors of the Catskill Mountains and beyond. Season after season, patent after patent, William Cockburn and his kid brother James surveyed and prepared maps which in themselves were objects of beauty and precision. However, in practical application the lines of their surveys wove a web which first expelled the land’s original inhabitants and subsequently ensnared generations of tenants on behalf of an increasingly land-rich provincial aristocracy.

The work of the Cockburn brothers was the work of colonization - with compass and chain they realized westward expansion rod by rod and blaze by blaze across the lands of countless native tribes in the name of the Province and those who ruled it. Each survey they prepared represented the definitive realization of tracts vaguely described in deeds and letters patent often prepared by proprietors who had never seen nor fully understood the scope of their own lands. The Cockburns were among those charged by the new owners with contextualizing and reporting on those lands in all their detail. In reports and maps William and James Cockburn related where respective lands were, what was on them, what merits existed for improvement, and how such improvement might be accomplished by the Cockburn brothers’ respective clients.

This work as vanguards of a new paradigm in land use and land ownership required infrastructure and support - itemized bills for the joint and individual labors of the Cockburns list everything from the total cost of provisions, payment for individual laborers who assisted the surveys, costs for searches at clerk’s offices, travel time, and the expenses for drafting reports and maps ultimately destined for the desks of the new lords of the Catskills: the Livingstons, Duanes, Van Rensselaers, Clarkes, and their peerage.

Such was the case with a map prepared by William Cockburn from a survey he completed in July of 1768 for Lieutenant Neil McLean, Doctor Malachi Treat, and Doctor Donald McLean, all late of his majesty’s service (probably in the Seven Years’ War). Treat and the McLeans were granted two tracts of land - one a large quadrilateral over the East Kill Valley in modern Jewett, the other an inexplicable shape made to fit against the bounds of the old Catskill Patent in modern Cairo. Cockburn’s map lists many anecdotes concerning the prospects of the land: the variety of timber, the prime farmlands, and the context of the land in relation to the river and “Blue Mountains.” The homes of several settlers are also shown, and the names of “persons employed in the survey” are interestingly related at the lower left of the map.

William Cockburn’s map of the McLean, Treat, and McLean Patent of 1768. Vedder Research Library.

The names of Cockburn’s assistants are as follows: John Pierce, Johannes Strop, [illegible] Young, William Hume, and John Wigram. Also shown on the map, just outside the bounds of the McLean and Treat lands in Cairo, appears the cabin of Johannes Strope on an upper reach of the Shinglekill; the house being more or less in the vicinity which local tradition bears out as the location of the massacre perpetuated twelve years after the map was produced. Whether the Johannes employed by William Cockburn was the ill-fated father or his eldest son is unclear, but it does illustrate the types of paying labor available to someone settled on the frontier in that time. It also places Strope on one side of the contentious conflict surrounding native expulsion caused by continued European encroachment on Native territory. Strope, as a participant not only in the settlement of the frontier but as a laborer in the surveys to perpetuate westward expansion, was engaged in a high-stakes contest long before the Revolution brought turmoil, and ultimately doom, to his family.

By Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian

Sources:

Cockburn, William. 1768. Map of Two Tracts of Land Granted to McLean, Treat, and McLean. Vedder Research Library. http://localhost:8081/repositories/2/resources/129

(the map which is the central object of the article.)Letter from William Cockburn to George Clarke, Philip Livingston, & Thomas Jones, 1797-06-15. Box 30, Folder 52, George Hyde Clarke Family Papers, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll66/id/2204/rec/2

(A letter representative of the advisory role of the surveyor in their relationship with the proprietors who retained their services)Elisha Andrews Affadavit and Statement, 1789. Box 30, Folder 32, George Hyde Clarke Family Papers, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll66/id/2086/rec/1

(An interesting document testifying to the tense relationship between the surveyors working on the frontier and native people sensitive to the encroachment perpetuated by their work.)Letter from William Cockburn to Goldsbrow Banyar Jr., 1805-03-12. Box 30, Folder 83, George Hyde Clarke Family Papers, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll66/id/2456/rec/1

(Another letter in which William Cockburn is seen to give direct advice on the ultimate division and utilization of land to facilitate its access and improvement.)Finding Aid for the Cockburn Family Papers, 1732-1864. Revised 2017. New York State Library Manuscrtipts and Special Collections. https://www.nysl.nysed.gov/msscfa/sc7004.htm

(Honor Conklin’s finding aid for the Cockburn Family Papers, containing valuable contextual and biographical information on the family.)

John Cantine's Map of Catskill

An examination of two segments of a map of Catskill from 1798 prepared by John Cantine.

This article examines the contents of two segments of a map digitized and made available to the public freely through the New York State Archives. All images are taken from downloaded versions of these maps, which are available to study through the links in this article.

~

John Cantine’s 1798 Map of the Town of Catskill is one of those fascinating documents which we in the history business call an “RRDCM” (meaning Really Really Dang Cool Map). Cantine’s map is one of three maps prepared in the late 1790s showing the southernmost towns of Albany County which were soon to be partitioned into the new County of Greene. The other two maps are linked here, but to follow the descriptions in this article you should jump right to the two links for John Cantine’s map.

Leonard Bronk’s map of the Town of Coxsackie can be viewed through this link: https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/36974

David Baldwin’s map of the Town of Freehold can be viewed through this link: https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/36974

John Cantine’s map of the Town of Catskill can be viewed through these links: https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/36925

https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/36924

Examining the eastern half of the Map of Catskill the first thing observers should note is that along the river at the northern boundary of the Town the small hamlet of Loonenburg labeled as “Esperanza” can be seen with the Zion Lutheran Evangelical Church drawn in as its most prominent building. The lower village which became Athens in 1805 appears just south of Esperanza as a solitary little structure which could quite possibly be the Jan Van Loon House which still stands at the south end of the modern Village (it’s the little yellow cottage by Route 385 so many of us are familiar with). This illustrates an odd bit of trivia: the Village of Athens was incorporated within the bounds of the Town of Catskill a year before the Village of Catskill was incorporated. I assure you that your friends will find this fact very interesting if you relay it to them at social gatherings.

Looking at the southern end of the map one can easily spot the location of the modern Village of Catskill, shown with a rough grid approximately reflecting the street plan of the rapidly growing community at the mouth of the Catskill Creek. Following the many roads leading from the Village going west and south it is interesting to note that John Cantine not only drew the roads from actual surveys (roads with an “x” on their route indicate that these are accurate to their surveys) but that he also included important homes, mills, and taverns at their proper locations. This is remarkable because many buildings now otherwise lost to time appear in their accurate locations. The mill shown on the Hans Vosen Kill is a perfect example of this. It was possibly the earliest mill built in Catskill in the late 17th century, and Cantine shows it just east of Jefferson Heights in 1798 — giving us a more complete idea of its whereabouts on this small tributary, as no physical traces of the site now remain.

Out in modern Leeds it is curious to note how sparsely developed the hamlet looks. Leeds at that time was not yet graced with its two large textile mills and still reflected its earlier agrarian appearance. Following the road west out of the hamlet (marked by Schuneman’s House and Mill) one can trace where it crossed the Catskill Creek at the Leeds Bridge at which point the road turned along the flats heading near to where the Barnwood Restaurant now stands on Route 23. In 1798 the Dutch Reformed Church stood just west of there on Cauterskill Road, and Cantine faithfully rendered the old church at that spot on his map. A NYS Roadside History Marker is all that remains to indicate that this important early Church stood on that spot.

The second half of the map isn’t as jam-packed with interesting sights as the eastern portion, but it is still an equally intriguing window into the cultural landscape of Catskill. Starting at the eastern or right side of the map a few points of interest are immediately apparent. First is the route of the Town’s southern boundary which, after proceeding westerly from the Hudson River at the Embought, reaches a point at the center of the small spit of land which once divided North and South Lake. From that point the line proceeds westerly on a slight adjustment where it ends at a point in the woods west of the Pleasant Valley Cemetery in Ashland, probably somewhere near modern Campbell Road.

This southern boundary intersects several roads, the strangest of which is shown halfway between North-South Lake and Pleasant Valley. The road terminates just north of the boundary line at a small cluster of cabins which Cantine carefully drew in. This small settlement seems like it could probably be somewhere in the East Kill Valley around East Jewett, and the road shown reaching it could be a spur of the old road from Mink Hollow, though the map doesn’t show enough detail to confirm the possibility. Resolving the conjectures I’ve made will take much more study.

In a separate essay titled “On The Mountain Top” I covered an explanation of the westernmost corner of this map where Medad Hunt’s farm and tavern stand was shown in Pleasant Valley. The year after this map was made Medad Hunt donated land nearby to create the first meeting house in old Windham. More extensive write-ups on this history appear in Rev. Henry Hedges Prout’s “Old Times in Windham” series which originally ran in the Windham Journal in the 1870s and was published as a compilation by Hope Farm Press in the 1960s.

No details are shown along the northern boundary moving west to east across the map until it reaches a cluster of roads at its far right edge near the Shingle Kill in modern Cairo. This lack of detail can be explained in part by the boundary intersecting a lengthy stretch of inhospitable terrain along the escarpment of the Catskills. The roads and hamlet shown at the eastern side of the map are actually back down in the valley, though to look at the map one would never know there were any mountains or other geographic features sans the few creeks and streams Cantine added for reference. I’m at a loss why he decided to eliminate such definitive geographic features, but it may be that he decided not to include the mountains because he had no accurate survey of them to base his rendition on.

Down in the valley the hamlet of Kiskatom (later Lawrenceville) is drawn in northeast of North-South Lake and is described as the “Settlement at Kiskatammiska.” This name is one of the many attempts to derive a phonetic spelling of a name applied to what was variously called the Kiskataminiska Patent granted to Henry Beekman and Gilbert Livingston in the 1710s. The original patent covered a stretch of several hundred acres north of Palenville running below the escarpment of the Catskills. This land was divided and leased by the Beekmans and Livingstons prior to the Revolution, so the homes and settlement shown here, unlike the ones on the Mountain Top, were relatively well established and several decades old by that time.

By Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian

A Sketch of Kaats' Kill

An early engraving of Catskill from the New-York Magazine is examined and contextualized.

In the September, 1797 edition of the New-York Magazine, or Literary Repository a fascinating engraving was presented as the frontispiece. The image was accompanied by a short paragraph which follows below:

“The plate annexed represents a view of Kaats’ Kill, in the state of New-York, on the west side of Hudson’s River, about 130 miles north of the city of New-York. This village contains nearly one hundred houses and stores, and is in a thriving condition. It has the advantage of a considerable extent of back country, which is rapidly settling by an industrious set of people. Vessels of 80 or 90 tons approach it from the Hudson through a creek. —The mountains in this vicinity, known by the name of the Kaats’ Kill Mountains, make a majestic appearance, and, it is said, furnish many things for the gratification of the curious.”

New-York Magazine, Sept. 1797.

There is of course a considerable amount to address even in this simple woodcut. Top on my list is the “controversy” concerning the composition of the engraving itself. In Field Horne’s 1994 book The Greene County Catskills: A History this image is included and captioned as showing Catskill, but the caption further states that it was engraved in reverse — hence the community being located on the “wrong” side of the creek. This is incorrect, and assumes the image shows Catskill from the east bank of the Hudson River. As the excerpt above insinuates, Catskill Landing (the village hadn’t been incorporated yet) was not visible from the Hudson because it was farther up Catskill Creek and hidden from the river by a bluff. Within a decade of this engraving’s publication the long dock and wharf we know now as Catskill Point would be constructed for several businessmen in the community, but even in the 1820s observers remarked that aside from the long dock and steamboat landing little of the Village proper was visible from the Hudson. It is more or less still the same way today.

Instead of showing Catskill from the other side of the river, this engraving actually shows Catskill from the opposite side of the creek. The landing for “vessels of 80 or 90 tons” described in the excerpt was at that time in the vicinity of modern Catskill Marina at the foot of Green Street below Main. The community grew up initially in that vicinity before spreading further along Main Street. To understand the composition of this scene imagine the artist standing somewhere along the stretch of West Main Street between Creekside Restaurant and the garage and office of the Greene County Highway Department. The artist used some license to compose a birds-eye view, but recognizable features include the hop-o-nose rock at the right of the engraving, the central bluff where the Prospect Park Hotel once stood and where the Friary is today, and the mysterious building that looks like a church but is actually the old Academy. The latter building appears on maps of the Village from the 1790s as standing above Main Street but below the crest of the bluff.

A detail from John Cantine’s extensive map of the Town of Catskill from 1798. The map curiously shows a prospective municipal grid at Catskill Landing, which at that time had not yet been incorporated as a Village. The new academy building, constructed following an initial subscription among residents of the landing, appears as a landmark labeled “accadimy.” Detail from Map NYSA_A0273-78_369B in the New York State Archives, viewable at https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/36925

For all of you on the Mountaintop the excerpt which accompanied this image should be of considerable interest. The image and excerpt were published during an intersectional period when the name of the Catskill Mountains was still in flux. There are maps published right up to the end of the 18th century which use “The Blue Hills” when referring to the Mountains, and this article calling them the “Kaats’ Kill Mountains” foreshadows the “Catskill Mountains” which would become their popular and official name.

Equally interesting is the editor’s final remark stating that the Mountains offered both a “majestic appearance” and “many things for the gratification of the curious.” The industrious people he spoke of as settlers in the backcountry were not the sort seeking pretty sights and relaxing getaways — what I mean to say is that the first settlers on the Mountaintop would probably have called the Catskill Mountains “inconvenient” rather than “majestic” and found the rocky soil and thick timberland anything but a “gratification for the curious.” If you do not want to take my word for this I implore you to try running a furrow anywhere in the Catskills and report back to me on the experience. All this is to say that the editor of the New-York Magazine, four years prior to the birth of Thomas Cole, was already sensitive to an alternative value in the scenery of the Catskill Mountains. Rather than being a place where profit only existed in lumbering, tanneries, and farming, the editor alludes to intrinsic value in the appearance of the place itself. Whether the writer ever lived to see his point proven is unknown, but within a century the biggest industry in the Catskill Mountains would be selling the region’s majestic appearance and gratifying the curious.

By Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian

Peter's Taken-Up Notice

A document advertising the capture of a runaway Slave named Peter by John DuMond of Catskill offers a glimpse into the collision of world and people during the American Revolution.

Taken up in the woods near Catskill the 22nd October 1780

A Negro man named Peter, supposed to be run away from his master,

he speaks nothing but English and his Mother Tongue, the former he speaks so

improper that he cannot be understood only here and there a word and the

latter is such a tongue that our Negros here cannot understand. We understand

by him (or at least we think so) that he has lived with one Rineheart

and that he was going to sell him on which the Negro run off, but

where Rineheart lives we can not learn. He is about six feet high

and about 26 years old, spare and ragged. Whoever proves [illegible]

Negro to be their property and paying charges may have him again

of the subscriber at his house in the District of the Great Imbought

in the County of Albany and State of New York —

October 25, 1780 John B. Dumond

So reads the entirety of a document written on the back of a piece of scrap paper which has been in the care of the Greene County Historical Society since 1966. John Dumond’s notice of the capture of Peter is a devastatingly incomplete window into the intersection of the lives of two men - one a relatively well-documented freeholder in the Great Embought District of Albany County, the other a young enslaved man whose life and existence are only testified to through the surprising preservation of this solitary piece of paper.

This notice is fascinating for myriad reasons, but chief among them is the anecdotal clue revealed about the status of the slave trade in New York at the time this notice was written. Specifically, the commentary on linguistic barriers is surprising because of its implications concerning the origin of people enslaved in the upper Hudson Valley during the late 18th century. John Baptiste Dumond himself was a landowner in Catskill who owned four people in the United States Census of 1800. Whether this was similar to the number of enslaved people in his household in 1780 is unknown, and unfortunately the Federal Census of 1790 offers no insight because the margin which tallied his slaves and those of his neighbors was destroyed.

The notice written by John B. Dumond of Catskill advertising the capture of the runaway enslaved man Peter. The text is reminiscent of notices published in newspapers, but it is unknown if this notice was ever put in print or distributed. Charles Anderson Collection, Vedder Research Library.

The number of enslaved people in Dumond’s household aside, it is interesting that they apparently possessed a common second language other than English or the still commonly spoken Dutch of this area. For that to have been the case these people couldn’t have been separated by more than a generation or two from people who were purchased through transatlantic or Caribbean slave markets. The isolating nature of enslavement in New York, where blacks were frequently the sole or one of only two or three enslaved people in a household, meant there was no broader community to help perpetuate cultural traditions and language. This, and the tendency of enslavers to separate children for sale at a young age, meant there were also few opportunities to pass on generational cultural identities once the enslaved arrived in the upper Hudson Valley.

That the runaway man in this notice was from a different language group and not fluent in English, Dutch, or the common language of the enslaved people in Dumond’s household is a possible clue that he was a survivor of the middle passage, stolen from his home and brought to a market in New York which even in the late 18th century was bolstered by an ongoing demand for imported slaves. Whether the runaway man Peter or Dumond’s enslaved people spoke Spanish, Portuguese, or different African languages may never be known, but the meeting of these people in this circumstance illustrates broadly the strange cultural collisions precipitated by chattel slavery.

Unrelated to the purpose of the notice is John Dumond’s closure with “State of New York” in the year 1780, one year prior to the conclusion of the Siege of Yorktown and three years prior to the signing of the Treaty of Paris. Whether this can be taken as evidence of Dumond’s patriot leanings is unknown, but the fact that he would bother to note “State” of New York rather than “Colony” on a notice such as this (unrelated to functions of the Revolutionary State Government) is perhaps illustrative of the transforming sociopolitical identity of the people in the Town of Catskill at that time. If that is the case it is doubly ironic that a freedom seeker’s flight would be hindered by a man concerned with the business of liberty and self-determination.

By Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian

Questions about anything in this feature can be directed to Jon by email at archivist@gchistory.org

An Early Scene of Athens

An early print of Athens and Hudson reveals both the old ferry canal and a window into America in the 1820s.

This article features an interesting print which comes to us from the digital collections of the New York Public Library. I was clued into the existence of this image by a friend across the river who saw a bound collection of these prints up for auction on Ebay. The Greene County Historical Society didn’t try to bid on the eBay listing, but I was able to find a free version online to satisfy our curiosity!

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "View of the Hudson and the Catskill Mountains" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-55c9-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

This view of Middle Ground Flats and the communities of Athens and Hudson come to us from a work by Jacques Gerard Milbert first published in Paris in 1828 titled: “Itineraire Pittoresque du Fleuve Hudson et des Parties Latérales de l’Amérique du Nord.”

Within the three volume set are 54 lithographed views of the Hudson River Valley. I found this particular view of note for one initial reason - it may be the earliest view available of the ferry cut or "canal" that was dug through Middle Ground Flats for the benefit of the Hudson-Athens Ferry in 1818. The canal was less than a decade old at the time the scene was composed, and shows a steam-powered ferry using the cut. At Athens today one can still spy the remnants of this canal from the Riverfront Park by discerning where the thinnest region of tree growth is on the now heavily wooded flats.

The steam ferry was an interesting inclusion by the artist, because Athens wouldn't receive its first steam ferry until the 1850s. Perhaps the person composing the scene thought a steam ferry would convey a better sense of the progress and affluence that was on display in the Hudson Valley at that time. What the artist would have actually seen was a "Team Boat" powered by several horses on treadmills which plied the same stretch of water.

The scene itself is composed from somewhere near Promenade Hill in Hudson at the end of Warren Street, and I find the artist’s inclusion of some Hudsonians having a leisurely picnic to be a very interesting feature of the scene. These well-dressed folks were part of an affluent up and coming merchant/leisure class that called Hudson and Athens home in the 1820s, and they are no doubt picnicking in a spot where they could look out on a scene they found beautiful and also had financial interests in. Perhaps one or two of the picnickers may have owned some of the ships sailing the river, while others on this picnic profited from trade of the goods being carried in the holds of those passing vessels. Still others may have owned and leased tracts of land in the distant Catskill Mountains.

“Four ships? Thats nothing - I’m exploiting the labor of seven tenant families in the Hardenbergh Patent!” - possible quote of a picnicker.

These leisure class picnickers are one and the same as the clientele who came to the earliest resorts of the Catskill Mountains; through their consumption of new art forms and materialistic diversions they would inadvertently help define the intrinsic value of the American wilderness while paradoxically continuing to exploit and industrialize it.

Cumulatively, Jacques Gerard Milbert’s stirring scenery, bustling traffic, carefree populace, and built landscape all conspire to make a definitive statement about what the United States was in the 1820s.

Questions and comments can be directed to Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian, via archivist@gchistory.org

An earlier version of this article first appeared in Porcupine Soup on March 12, 2021.

French Émigrés and the Plan of Esperanza

The story of three French Émigrés who joined in the creation of a mysterious plan for the City of Esperanza at modern day Athens, New York in the 1790s.

In the tumultuous years following the commencement of the French Revolution in 1789 the United States played host to a rotating menagerie of representatives, expatriates, and refugees from the young French Republic. The influential Livingston family, representing the epicenter of society and politics in New York, accepted several stateless Frenchmen into their graces in the early 1790s - chief among them surveyor/architect Pierre Pharoux, visionary Pierre de la Bigarre (aka Peter DeLabigarre), and artist Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin.

These three men, acquainted as countrymen in a foreign land and involved in overlapping ventures, are celebrated by modern scholars for a number of different and notable achievements. Despite the esteem with which they are held in academia, their influence is often overlooked or entirely unknown in the upper Hudson Valley where these men spent considerable time. This is surprising given that these French émigrés were integral to the story of Esperanza, the 1794 land speculation undertaken by Edward Livingston, John R. Livingston, Ephraim Hart, Elihu C. Goodrich, and Brockholst Livingston to create a new planned city where the Village of Athens now stands.

How these Frenchmen managed to remain omitted for so long from the history of Athens is a complicated tale, but matters were made worse by William Pelletreau. It appears that Mr. Pelletreau, who wrote the remarkable and authoritative chapter on Athens for the 1884 History of Greene County, made a surprising transcription error from an early map. That map, engraved circa 1795 showing the proposed city of Esperanza, was a fascinating artifact complete with street names and designated civic spaces. The copy Pelletreau examined was likely one of two copies which were accessible to him in the 1880s. Neither local version of the Plan of Esperanza included a title nor attribution naming the creator, though tradition brought down to him tale that the map was produced by a mysterious “P. Pharmix.” That name, as it turns out, was a misconstrued reimagining of the surname Pharoux, though this connection has only been definitively proven by scholars in the last thirty years.

This is Greene County’s record copy of the Plan of Esperanza. The map’s legend does not include an attribution naming Pharoux, nor does it bear the cryptic name “Pharmix” which William Pelletreau attributed as the map’s creator. The map is glued into Map Book One, and there may be obscured writing on the map which can no longer be read. It is very likely this local copy may have been the one Pelletreau used as a reference when writing his chapter on Athens in Beers’ History of Greene County.

Unknown, from Pierre Pharoux. A Map of the New City of Esperanza. Scale not given. Hudson Valley, c. 1795. Image scan courtesy of Greene County Real Property Tax Services and the Greene County Clerk’s Office.

Pierre Pharoux is the most tragic of the three émigrés involved in the Esperanza speculation. Originally from Paris and a participant in the earliest years of the French Revolution, Pharoux is celebrated today for the journal he kept of his time in America and for several unusual civic and architectural plans he produced for affluent clients in the Hudson Valley. He originally came to the United States as one of the surveyor-agents working on behalf of the La Compagnie de New York which was organized to settle refugees of the French Revolution on land in modern-day Lewis and Jefferson Counties. Pharoux’s journal offers scholars detailed insight on his projects and the social circles he moved in during his time in the United States, but his work was cut short when he drowned in a rapids with several others in September of 1795.

It is likely Pharoux’s death, the unrelated failure of the Esperanza venture, and the misattribution of the map he helped create conspired to obscure his contributions for so long. Fortunately recent attention given to an auctioned engraving of his Plan of Esperanza and the increased availability of far flung digitized collection items at the Huntington Library and National Gallery of Art have served to reestablish the significance of his work in the Hudson Valley in the years prior to his death. An authoritative transcribed version of his Journal was also published by Cornell University Press in 2010.

The engraver of the Plan of Esperanza was Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin, a friend of Peter DeLabigarre (the third French émigré of this tale) who is most celebrated for his portraits. Acquainted with the upper crust of New York society, Saint-Mémin was able to produce engraved portraits of dozens of prominent citizens and acquaintances as well as portraits from life of several of the Founding Fathers. His friendship with and early patronage by John R. Livingston makes Saint-Mémin’s participation in the creation of the Plan of Esperanza no small coincidence, as Livingston was one of the principal stakeholders in the venture. Whether the high-born Esperanza speculators retained Pharoux and Saint-Mémin individually or jointly is unknown, but Pharoux’s journal includes mention of passing along drawings so that Saint-Mémin could produce an unknown number of copies which today are cherished rare collectibles. It is possible Pharoux’s drawings are the same ones which which are now available as digitized manuscripts through the Huntington Library, though this is unclear.

Peter DeLabigarre is the fascinating figure who completes this émigré trio. Alf Evers spends an entire chapter of his book The Catskills on him — specifically the ventures DeLabigarre undertook in the Catskill Mountains for the benefit of science, mankind, and personal finances. Those ventures, done under the auspices of his friend and neighbor Chancellor Robert Livingston, included the notable and likely first recorded ascents of Overlook Mountain and Kaaterskill High Peak. DeLabigarre even named the latter “Liberty Cap” in his reports to celebrate America and France’s kindred Revolutionary spirit. DeLabigarre also famously tried to promote the cultivation of silk worms on the Livingston’s estates and was also a close friend to Edward, youngest brother of Chancellor Livingston and another member of the group of speculators at Esperanza.

Pierre DeLabigarre’s so called “Liberty Cap” at left of range above Kaaterskill Clove. DeLabigarre made what is probably the first recorded ascent of today’s High Peak on an expedition in the 1790s. He would have been able to view the mountain from his accommodations in Tivoli on the east bank of the Hudson. Palmer Photo, 2021.

Among DeLabigarre’s other ventures was the creation of a proposed town on the banks of the Hudson to be crowned by his estate “Chateau de Tivoli” and lying nearby the lands of Chancellor Livingston at Clermont. While his proposal for the town never panned out, the Tivoli of today is still known by the classical name granted to it by its famous émigré resident. The only other remnants of DeLabigarre’s Tivoli dream endure in an engraved map made by none other than Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin, and it is unknown if the actual survey work was conducted by DeLabigarre or by Pharoux as a talented mutual acquaintance. As the plans of Esperanza and Tivoli were being produced at virtually the same time and by people in the same circles it would be unusual if Pharoux wasn’t involved with both.

It is thanks largely to the research and digitization efforts of several major repositories and an auction house that the identities of the creators of the Plan of Esperanza are now definitively known. As such, this information certainly serves to contextualize certain aspects of the Plan of Esperanza which were of obvious interest even in the 1880s to William Pelletreau. In the 1884 History of Greene County he makes note of the inclusion of streets named Liberty and Equality, a facet of the map now demystified with the revelation that its creators were men endeared to the democratic principals of the French Revolution but not the violence that defined much of the 1790s which precipitated their removal to the United States.

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Pharoux’s Plan of Esperanza is the part of the plan William Pelletreau didn’t know existed when he wrote his history in the 1880s. Not only did Pharoux prepare a map as surveyor, he also applied his visionary concepts of architecture and civic planning in a selection of drawings which were also engraved by Saint-Mémin to accompany the map. Saint-Mémin’s engravings of those buildings are now digitized and available online through the National Gallery of Art, and as a collection testify to a comprehensive vision for Esperanza which until recently has never been fully grasped by local historians. The scale and vision of the plan, coupled with an understanding of the background of the remarkable people involved, leaves more questions than answers as to why Esperanza failed. By 1801 portions of the proposed but unrealized City of Esperanza would be subsumed in a competing speculation led by Isaac Northrup and several businessmen from Hudson, resulting in the highly successful incorporation of the Village of Athens in 1805 as Greene County’s first fully realized planned community.

Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin, Esperanza Church, 1795. National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran).

Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin, Esperanza Market, 1795. National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran).

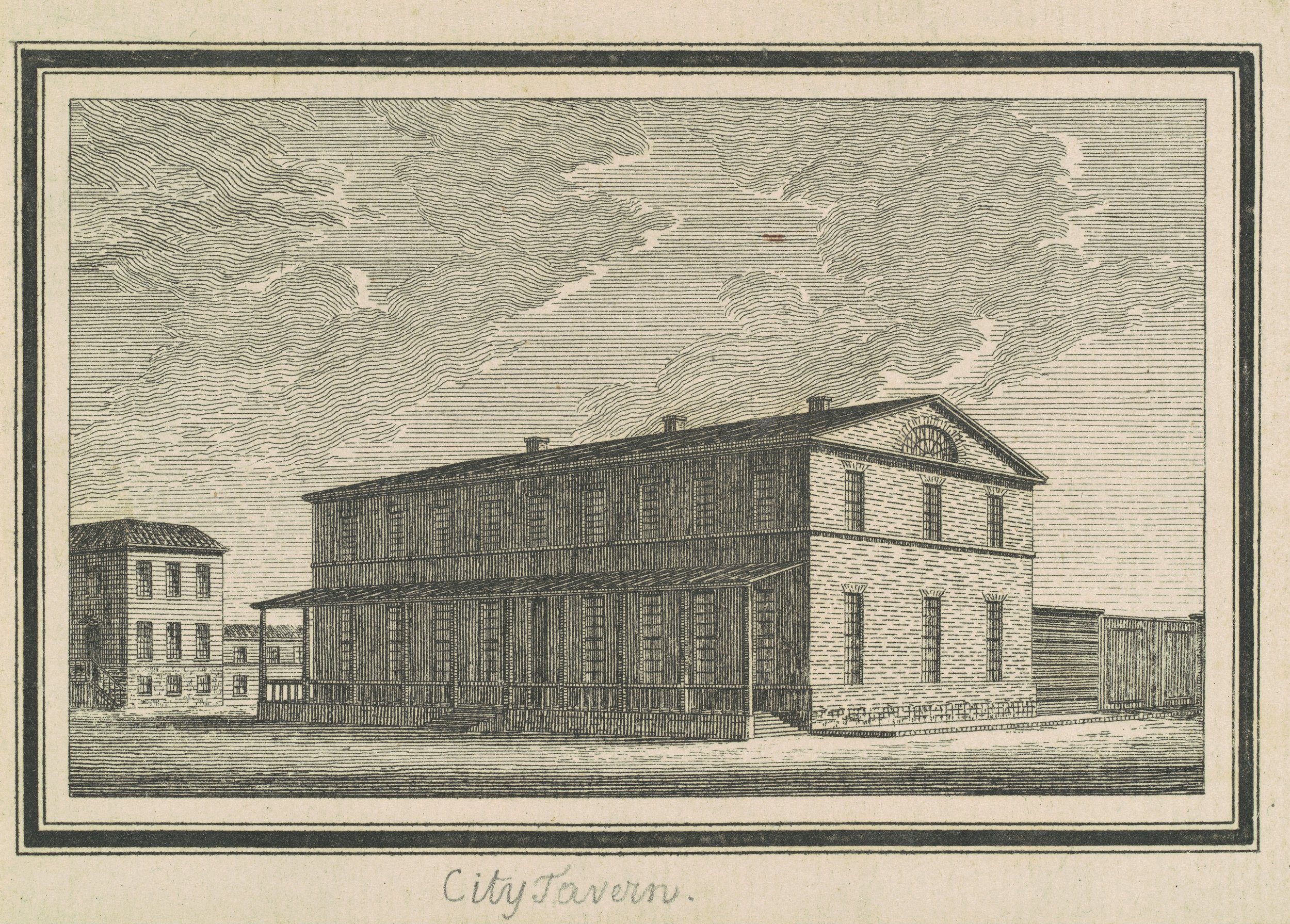

Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin, Esperanza City Tavern, 1795. National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran).

The Three Images above were all engraved by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin as part of his efforts to prepare enticing promotional material in partnership with Pierre Pharoux for their patrons who were developing a planned community on the banks of the Hudson at modern Athens, New York. These buildings, (which were never realized) offered potential investors a glimpse of the beautiful opportunity offered by the latest trends joining modern architecture with urban planning - in essence realizing the ideals of the new American republic in brick and mortar.

Questions and comments can be directed to Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian, via archivist@gchistory.org

Stereographs of the Catskills

A discussion of stereographs and the early practitioners of stereography in the Catskills.

Rapid advancements and innovation continuously redefined the field of photography throughout the mid-19th century. Improvements in camera and lens designs, changes in chemistry and technique, and the ever-growing appetite of the viewing public for affordable quality images drove photography from fringe curiosity to the forefront of mass media within twenty years of its introduction. Stereography, a photographic technique by which the viewer is tricked into perceiving a single three dimensional scene from two juxtaposed images, was an early and almost magical addition to the repertoire of accomplished photographers in Europe and America. Within a decade following the first demonstrations of the principle of stereopsis by Charles Wheatstone in 1838 there were practitioners utilizing the earliest and most rudimentary photographic techniques to render people and scenes in three dimensions with varying degrees of success. Continued refinement and the increased availability of cheap stereoscopes allowed stereographs to evolve from fringe luxury items to affordable and ubiquitous parlor companions around the world.

In Antebellum America the Catskills were already a celebrated and storied vacationland. These relatively accessible mountain environs had been elevated to something of a national treasure in works by painters and authors, so the area naturally attracted photographers almost immediately following the world introduction of the daguerreotype. A choice few of these practitioners composed early stereographs which survive to this day as one-of-a-kind expressions of their technique and artistry. These stereographs were a fascinating product. Using a stereo camera two lenses would simultaneously expose subtly different angles of the same scene on a wet (or later dry) photographic plate to create an image. Using those two lenses spaced roughly six centimeters apart allowed the camera to “see” much the same way the spacing of our eyes facilitates perception in three dimensions. Early practitioners apparently sometimes attempted this with a single lens by moving the entire camera slightly. The end result would appear like the first example below.

“Catskill Mountain House and Mr. John Allen’s Dog” by S. Root, 1854

This stereo Daguerreotype of the rear entrance to the Catskill Mountain House was audaciously composed by Samuel Root while visiting in 1854. Now heavily damaged with age, the two daguerreotypes within were not composed synchronously, leaving the image exposed in a different position on each plate. Even within a properly seated mounting the stereo effect would be minimally apparent, as the focus of each image is also substantially different. Daguerreotypes are one-of-a-kind, meaning Mr. Root’s effort to compose and mount the image resulted in only one salable item for his troubles. Collections of the Vedder Research Library.

“The Lower Falls at Kaaterskill” Photographer Unknown, c. 1855

This damaged stereo Ambrotype of the lower falls at Kaaterskill represents an intersectional period of innovation in stereoviews. The Ambrotype is essentially a glass negative mounted on velvet to create a unique single positive composition. However, unlike the stereo Daguerreotype by Samuel Root, this image was composed using a single treated plate and a stereo camera. Collections of the Vedder Research Library.

“The Mountain House from the North Mountain” by Frederick Langenheim, 1855

Frederick Langenheim of Philadelphia patented a technique to render bright, translucent images backed by frosted glass in 1850, calling it the Hyalotype. This 1855 image of the Catskill Mountain House, one of a trove of stereo views Langenheim composed on different media, offered lifelike luminance when viewed by a window in addition to the nicely executed stereoptic effect. The Hyalotype, an advancement of the Calotype technique, allowed Frederick and his brother to market copies made from an exposed negative through a form of contact printing. Collections of the Vedder Research Library.

Stereographs, like all other photographic styles, benefitted immensely from the innovation of new and improved negative-positive print techniques. The Langenheim brothers of Philadelphia had met with considerable success using the Calotype technique and the Hyalotype technique (which they patented) to offer stereo views on paper and glass prior to the Civil War, but the albumen printing technique finally made negative-positive printing accessible broadly to the photographic community on the eve of the Civil War. As the Civil War raged people across the nation were suddenly able to purchase images of great statesmen and generals, or commission multiple duplicate images of themselves and friends for nominal fees. This simultaneously made photography more affordable for the subject and more lucrative for the photographer. The stereograph was adapted quickly to an albumen print format with remarkable success, and the Catskills suddenly became an affordable destination which could be comfortably reached from anywhere in the country by simply sitting in the parlor with a stereoscope.

Oliver Wendell Holmes designed this affordable stereoscope before the Civil War and never patented it, allowing copycats to make these viewers affordably for the benefit of a public craving stereograph images. Mounted in the viewer is an E. & H. T. Anthony stereograph c. 1873 showing ice formations at Kaaterskill Falls.

Among the most prolific of the firms creating and publishing stereographs of the Catskills were Edward and Henry T. Anthony (E. and H. T. Anthony & Co.) of New York and John Jacob Loeffler of Staten Island. By all indications the Anthony brothers were the earliest of the two, but their portfolio was far more encompassing than just selling scenery of the Catskills. They funded and published some of Matthew Brady’s work during the Civil War, and sourced images from across the country in an effort to appeal to a broad audience who may not have necessarily had the money to travel but had the money for a stereograph. Edward and Henry Anthony’s main source of income was in the sale of photographic supplies, and they were one of the largest US-based sellers in the mid-19th century.

“Looking Down the Kauterskill, from New Laurel House” Scene 4202 from The Glens of the Catskills by E. & H. T. Anthony & Co., c. 1865; Collections of the Vedder Research Library, item PC-0000-0022-0034.

The earliest of the Anthony brothers’ Catskill Mountain scenery may date to the Civil War, but their work, much like that of J. Loeffler, is exceedingly difficult to precisely date. This is because much of their promotions, sales material, and business records apparently longer exists or are otherwise inaccessible — so while we know they most certainly had a collectible stereograph series called “Glens of the Catskills,” we don’t know precisely when they first advertised it or when they took the pictures to create the series. In many cases older images from other series could be incorporated into new collectible series, meaning an image originally published in the late 1860s could still be making the rounds in the 1880s if it was a good seller.

The Getty Museum dates some of E. and H. T. Anthony’s stereographs as early as the beginning of the 1860s, meaning that at least a selection of the Anthony portfolio was created using wet collodion plates that had to be prepared, exposed, and fixed on-site in the woods where the picture was taken. Their groundbreaking and unusual winter scenery, which they published several versions of in the 1870s, were probably done using dry plates which would have been far more forgiving in freezing temperatures. In fact the advent of dry plate stock in the early 1870s may have been the only thing that made their very novel winter series of stereographs possible, hence their appearance following the invention of dry photographic plates.

“View from Sunset Rock, looking East” Scene 265 from Artistic Series: Winter in the Catskills by E. & H. T. Anthony & Co., c. 1873; Collections of the Vedder Research Library, item PC-0000-0022-0003.

“Caves of the Ice King under Kauterskill Falls” Scene 274 from Artistic Series: Winter in the Catskills by E. & H. T. Anthony & Co., c. 1873; Collections of the Vedder Research Library, item PC-0000-0022-0009.

John Jacob Loeffler’s work in the Catskills, while more or less concurrent with the Anthony Brothers, is even more difficult to date because there is comparatively much less information available about him. A subsequent article will consider one of his images, the location it was composed, and how this can be used to facilitate an understanding of Loeffler’s artistic vision and a rough date of composition.

By Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian

Questions and comments can be directed to Jon at archivist@gchistory.org

A Palenville Footbridge

Identifying the location of John Jacob Loeffler's stereo view "Foot Bridge Near Griffin's Store" taken in Palenville, NY.

E. & H. T. Anthony & Company’s dominance in the Stereoviews market in the years following the Civil War left plenty of room for niche photographers to make their mark. John Jacob Loeffler of Tompkinsville, Staten Island, was one such practitioner who availed himself of the chance to compose stereographs of scenes sometimes off the beaten path and overlooked by his peers. Across the Catskills he captured countless images of both the majestic and rustic, creating what would become an authoritative catalog of some of the most iconic corners of this celebrated vacationland. All indications seem to point to his catalog of work being considerable in scale, but today relatively little is known of him and his artistry. The Library of Congress offers seven images by him in their catalog, and a few miscellaneous websites purport to have scattered selections of his various stereographic series.