GREENE COUNTY HISTORIAN’S BLOG

Rolling Down to Old Maui - Part Two

The story of Catskill native Joseph Allen DuBois continues after sailing from New Bedford on a whale ship in September of 1851.

It’s a damn tough life,

full of toil and strife,

we whaler-men undergo…

~

Azore Islands

Sep. 20th 1851

“Dear Sister,

I suppose a little description of

the way we live on board the Cambria would

interest you a little. We sailed from New Bedford

on the 3d Sept. the vessel manned by 18 foremast

men, 4 boat steerers, cook, carpenter, steward,

cooper, 3 mates, and Captain…”

- Letter of Joseph A. DuBois to his sister Mary DuBois.

This is part two of a series. Read part one here.

The port of New Bedford was home to two religions, and monuments to both rose high above the rooftops of the town. As Joseph DuBois approached the first things he saw were white church steeples rising above the horizon: ubiquitous symbols of a protestant god who was worshipped every Sunday by New Bedford’s old New England families. By the time he had passed through town and reached the wharves the skyline had taken on an entirely different aspect, and the white steeples were long lost in a tangle of towering masts and rigging so thick that their shadows offered relief from the blazing noonday sun. Those masts rose to the heavens in adoration of the god Commerce, an ancient deity in whom the faith of the community rested the other six days of every week.

“The Whale Fishery” from a photograph by T. W. Smillie showing whale ships at New Bedford. Collections of NOAA.

Commerce wielded a terrible power, and the livelihoods of ship owners were made or broken by the waxing and waning fortune which Commerce bestowed on them. This is to say nothing of the sailors themselves; the vital components of the ships that were New Bedford’s lifeblood. These were brave men who died in the hundreds on distant seas in the name of the ships and owners they served, all drawn to service on the ocean for reasons as diverse as the seas they sailed. The protestant churches in New Bedford filled every Sunday with sailor’s widows whose lives were shattered in the name of profit, while in the pews ahead of them sat the ship owners who heeded only their profit margins when a vessel never returned from the other side of the world.

All of this was undertaken in the name of Light. Whale oil, a bright and clean burning combustible, illuminated the meteoric industrial progress of the antebellum United States. Beside the steady glow of lamps filled with New Bedford whale oil draftsmen completed designs of the nation’s great factories, engines, and furnaces; poets, scholars, and thinkers drafted their treatises and manuscripts in the lonely hours of the night; ships were guided home in the dark carrying the riches of international trade by newly constructed coastal beacons. America was aglow at all hours, and it was thanks to hundreds of ships from New England ports manned by thousands of men employed in one of the most high-stakes industries of their era. For those of stout constitution and steady conviction there was always work to be had on the deck of a whaler, and though the work was brutal there were also few better avenues to fortune and adventure.

Joseph quickly found a berth on board the Cambria, a successful whaler which had already made several voyages to the northern waters of the Pacific and returned much to the enrichment of the crew and her owners. Such voyages had become a necessity by the 1850s - overfishing of the North Atlantic had depleted populations of Right and Sperm Whale to the point that it was no longer economical to try hunting them there. The Pacific was virtually untouched though, and a lucky captain could fill his hold with enough whale oil that he could practically retire on the earnings. Thus, what had once been an undertaking of several months had transformed into voyages that lasted as long as four years, and the tolls and perils were too numerous to contemplate.

Captain William Cottle addressed the crew once the Harbor Pilot departed on the afternoon of September 3, 1851, leaving Joseph with the impression his new boss was a gruff but fair man of the sort particular to that line of work. Cottle’s First, Second, and Third Mates stood alongside him as he spoke:

“Now men, I suppose you know what you shipped for - you have shipped for the voyage.

Do your duty and you will be used well. You shall have enough to eat and drink as long as it is

in the ship. I will have no swearing or fighting. These are my officers [pointing to the mates],

see that you obey them.”

- Letter of Joseph A. DuBois to his sister Mary DuBois.

It then fell to the Mates to choose their watches. The Captain and First Mate had their pick of the most experienced sailors for the Starboard watch, the Second and Third Mates the remainder for the Larboard watch. Each watch alternated four hours above deck and four hours below deck for the duration of the voyage, sleeping when the opportunity arose or passing the hours mending clothing, writing or reading, and occasionally engaging in artistic pursuits unique to whalers of the era.

It should be stated that while the Cambria was owned by a New Englander and hailed from a New England port, the crew of it and whalers like it were often a curious mixture of ethnicities and languages, and there was no guarantee that the English spoken by the ship’s officers was the tongue of the men in the bows. Hawaiian Islanders, African-Americans, Scandinavians, and every nationality and creed in between found their homes between the decks of 19th century whale ships. The plurality of this culture of foremast men was something entirely foreign to green sailors like Joseph Dubois raised in the homogenous backcountry of the eastern seaboard. Richard Henry Dana, in his memoir Two Years Before the Mast, dwells on the topic at length noting the way in which this melting-pot culture was variously adopted by those who signed on ships bound for the Pacific. For Joseph Dubois, this first dose of culture shock was merely preface to the wonders he would witness over the next three years of his life.

The Cambria made short work of its voyage south along the coasts of North and South America, and Joseph wrote enthusiastically to his sister Mary of the routine he and his shipmates maintained at sea. Making good time and with ample provisions there was no need for the Cambria to call frequently at ports on that first leg of the voyage. As such, Joseph’s letters could not be posted regularly. Instead they were prepared with other mails of the crew to be passed along if a ship was encountered bound in the opposite direction - ideally a fellow whaler heading home to Massachusetts. Such encounters on the high seas were not infrequent, and for crews of whalers returning home from the Pacific after two years away the opportunity to get news as fresh as last month from New Bedford was cause for celebration.

At the sight of a fellow American whaler on the horizon the Cambria would spring to life - changes in heading were called out as the foremast men rose into the rigging. Sails were adjusted, and the anticipation would build as wind and tide slowly closed the gap between the vessels. Mile by mile this waiting would continue until the range had closed to the point where shouts of salutation could be heard over the breeze. Captains then exchanged pleasantries through speaking trumpets, crew members might recognize a familiar face on the opposite deck, and mail and news would be sent across if conditions permitted. Nearly every letter Joseph sent was prefaced by such a ceremony, and each was accompanied by the hope that the passing vessel to whom that mail was entrusted would return home safely.

Exterior fold of Joseph A. DuBois’ letter of 27 October 1852 mailed to his parents at Catskill from the island of Maui. Katharine Decker Memorial Collection, Vedder Research Library.

The sole reason the Cambria found itself so far from home was always foremost in the crew’s thoughts, and as the ship made its way from the Azores southward towards Cape Horn whale were spotted on a daily basis. These sightings precipitated a frantic mobilization of both the Starboard and Larboard watches, as any sighting of whale meant an opportunity to begin filling the Cambria’s hold. The quicker that hold was filled, the sooner the vessel could return home. Whale ships were really nothing less than floating factories designed for the production and packaging of whale oil, and Joseph wrote extensively in one of his letters home concerning the process by which the Cambria was transformed following the sighting of a whale:

“Aboard whale ships there is a man on the main and fore

royal mast on the lookout for whales…

…and hardly a day passes without a cry

from the mast head of ‘There she blows!’ ‘There she

breaches,’ ‘Whereaway’ yells the captain, ‘4 points off

the weather bow, sir.’ In a moment the captain is

aloft with his spy glass. The boat steerers spring into the

boats and clear away every thing in readiness for

lowering - ‘Let her luff’ sings out the captain from

the mast head, ‘Let her luff, sir’ says the man at the

helm. Then comes, ‘haul down main and fore top studding

sails, clew up main and mizen royals, brace the main yard,

brace the cross jack yard, brace the fore yard.’ The

ship is now standing for the spot where the breaches

were last seen, all hands looking eagerly over the

side. After waiting about an hour and no signs of any

fish, then comes the captain slowly down the rigging

singing out as he comes ‘square the yards,’ hoist

away main top gallant and fore top gallant studding

studding sails and in a moment the ship is again

on her course and all hands growling away at the

luck and wishing themselves every where else but on the

ship. The foremast hands are mostly green and it is fun

although I am as green as most any one of them

to see some of them perform.”

- Letter of Josep DuBois to his sister Mary DuBois

By the summer of 1852 the Cambria had reached the Northern Pacific and given successful chase to whales in the waters near the Bering Sea. In those instances, the whales sighted by the lookouts were still at the surface when the Cambria was luffed, and the boat crews (similarly divided among the boat steerers like the watches had been divided among the mates) were dropped into the water where the crews could give chase by oar. The Cambria carried four of these whaleboats on davits from which they could be lowered at a moment’s notice.

“American Whaler” by Currier and Ives, c. 1860, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Rowed by a diligent crew a whaleboat could rapidly overtake a recently spotted pod of whales, whereupon harpoons would be thrown in an attempt to secure the whaleboat by a long line to any whale presenting itself on the surface. This is where the chaos of the hunt ensued. When a whale was harpooned it generally sounded - diving deep in flight from danger - and it was a gamble by the whaleboat crews whether they had enough line attached to the harpoon that the whale would cease its dive before the line played out. If the whale drew it all up an inattentive crew could find their boat shattered and drawn underwater in these initial stages. If the whale didn’t sound too deep then the boat would be dragged across the surface, still connected to the whale, as far and as fast as the whale could muster in a circumstance known colloquially as a “Nantucket sleighride.” The idea behind such a gamble was that the stress of a forced flight would tire the whale out and bring it back to the surface exhausted, and it often worked perfectly. Once a whale came up, harpoons with lance-like blades would be used to finish the animal off, but the danger wasn’t necessarily over. In some instances a whale with fight left to give could smash unsuspecting boats as they came alongside, often killing boatmen and making good an escape.

Assuming this complex operation occurred in typical fashion, the carcass of a recently killed whale would then be brought back to the whale ship where the process of flensing would begin. If the smell of mountain tanneries was disagreeable to Joseph DuBois, then the sights and odors of flensing and trying a whale would have been downright offensive to the senses. It was terrible and dirty work. As sharks circled the floating carcass, made fast to the side of the hull with hooks and ropes, crewmen would use long blades to cut away the layer of blubber, a form of subcutaneous fat, that surrounded the whale’s body. These long strips would be brought on deck in a mess of blood and gore where they would be further cut up and dropped into try pots on top of a roaring oven. As the fat was rendered into oil, the ship’s cooper would make ready barrels in which the oil would be stored for the voyage home. In the 1850s a gallon of whale oil could fetch over $1.50, and it wasn’t uncommon for a whaler to return home with an $80,000 cargo if she was a larger ship.

“A Ship on the Northwest coast of America cutting in her last right whale” By Henry Wood Elliot, 1887. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Such work was exhausting, and it took a large number of successful kills to generate enough whale oil to make a pacific voyage marketable. Having sent no letter successfully since the end of December 1851, the next letter Joseph DuBois’ parents received at Catskill was from the Island of Maui dated the 27th of October 1852. After an arduous summer spent sequestered aboard the foul confines of the Cambria the island of Maui must have seemed doubly so the tropical paradise which the more seasoned crewmen of the Cambria had regaled their shipmates with stories about. Fresh provisions of all varieties in abundance, open space to walk, fresh air, and ships in the harbor bringing news from far and wide must have made Maui seem a mecca in the midst of the unending empty Pacific.

The Cambria remained at Maui from the 27th of October until the 12th of November before sailing to make good on fishing opportunities the South Pacific offered in the winter months. The smell of flowers and damp earth on the breeze lingered with the ship for a while after the island had disappeared from sight, a last reminder to the crew that their brief respite had not been a dream. In a letter Joseph sent home immediately prior to departure he said they anticipated arriving home in thirteen to fourteen months.

“Whaler off the Vineyard” by William Bradford, 1859. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Part Three will follow.

- Jonathan Palmer, Deputy Greene County Historian

Banner image is “La Baleine” by Ambroise Louise Garneray c. 1840. Public Domain.

A Brief History of Catskill's Newspapers

The Greene County Legislature votes to break ties with the Daily Mail, and the author offers some history of Catskill’s newspapers for context.

The recent resolution of our County Legislature to cut ties with the Catskill Daily Mail is a decision much lamented and hotly contested by the citizens of Greene County. Political divisiveness, speculations on the quality of the Daily Mail itself, and debates over the relative accessibility of materials published by the newspaper became fair game in the online discussion boards which are slowly becoming the unfortunate standard in interpersonal dialogue among neighbors. It is arguable that this moment was long in the making, and despite your feelings on it the year 2020 now marks the first time since 1792 that local residents won’t be able to get news of local government from their hometown paper.

We should get one thing clear right from the get-go. The Daily Mail has not been in business since 1792 as their masthead claims. That distinction instead belongs to a paper originally titled the Catskill Packet, which many of you had the pleasure of reading when it was last printed under the banner of the Greene County News - our final and now-defunct weekly paper. The Daily Mail is therefore something of a usurper to the legacy of the Packet, as the former was begun in the 1880s as a publication of a slightly more elevated quality than your typical gossip rag. The news the Daily Mail originally ran was of varying quality, and the pressure to print daily content meant that much material of little substance got printed to fill columns. The summer tourism industry here and the voracious appetite of the populace for news of all sorts meant the Daily Mail was guaranteed success in their gamble to edge in on the business of the big weekly papers, and as fortune would have it the Daily Mail ended up outlasting all the competition, claiming the distinction of having been published since 1792 primarily because there was no competitor left to challenge the ridiculous claim.

For most of Greene County’s history there has been more than one paper published in the County Seat at Catskill. When Mackay Croswell began printing the Packet in August of 1792 he did so as much to get a lead on the competition as he did to fill a need in the community. He experimented with the title of the Packet between 1792 and 1804, finally determining that the Recorder sounded like the most reputable banner to print his news under. At this early date the Recorder was not a political rag - Croswell published national news and local notices, and folks did their politicking at the tavern instead.

Notice of a meeting to form a society for the prevention of horse-theft at Catskill from an early edition of the Packet, c.1800. To my knowledge there have been no recent thefts of horses from Main Street in Catskill, which testifies to the efficacy of that Society.

The end of the war of 1812 commenced a period of great upheaval in American politics. As the last of the Founding Fathers retired and passed away in the 1820s a new generation of career politicians rose to take their place. These men, interpreters rather than framers of the Constitution, learned rapidly to utilize newspapers as political weapons which could polarize their constituents and win elections for their party. In Catskill, the Recorder met with an onslaught of competition beginning in the 1810s. Competition reached a fever pitch in the midst of Andrew Jackson’s Administration in 1831 when the Recorder’s bitter rival the Messenger first commenced printing. A perusal of a gazetteer from 1860 actually lists more than ten papers which were printed in Catskill during that fifty year span - an unbelievable notion when one considers that today the Daily Mail, our only “Catskill” paper, maintains neither offices nor print shop here.

I’ve listed the titles of some of those papers here just for your entertainment:

The Catskill Packet (Croswell)

The Catskill Recorder (Croswell)

The Catskill Recorder and Greene County Republican (Faxton, Elliot, Gates)

The Catskill Recorder and Democrat (Josebury)

The American Eagle (Elliot)

The Catskill Emendator (Unknown)

The Greene and Delaware Washingtonian (Kappel)

The Middle District Gazette (Stone)

The Greene County Republican (Hyer)

The Catskill Messenger (DuBois)

The Greene County Whig

The Catskill Examiner

The Catskill Democrat

The American Eagle/Banner of Industry (Baker/Van Gorden)

The Catskill Democratic Herald

The Recorder and the Messenger, the great rival papers of Catskill during the Jacksonian Period.

The Recorder and the Messenger’s editors hated one another, mainly because by the time the Messenger began printing in 1831 the Recorder had become a firmly Jacksonian newspaper. The editors unabashedly endorsed Jacksonian candidates for local, state, and Federal office, and the Messenger, in an attempt to balance the scales, quickly became the opposition paper allied with the rival Whig Party. Insults between the rival editors were published in every weekly issue, and considerable sums of money were offered in wagers on political contests by the papers themselves. It was a time of absolute chaos, and while I’m fairly certain the Recorder was the publication of record for the Greene County Board of Supervisors this would have mattered little to most citizens, as the Messenger and Recorder vied regularly to publish important news ahead of the other concerning elections and caucuses.

A typical editorial comment concerning the quality of the Recorder as published by the Messenger circa 1840.

In the years following the Civil War the Messenger changed its name to the Examiner, and the rivalry between it and the Recorder diminished in its public visibility considerably. In 1938 the two rival papers would combine to become the Examiner-Recorder, publishing quality content with a team of reporters and press photographers that brought the professionally of the paper to new heights. During this period the Enterprise and Daily Mail were also being published locally, making three major newspapers from which citizens could pick the content of their choice.

In 1962 the Examiner-Recorder merged with the Coxsackie Union-News (a similar weekly merger formed by two old rivals) and transformed into the Greene County News, which would finally fall victim to market pressures and the Daily Mail in the 2000s. A full review of the details of this late period in the history of Catskill’s papers is worthy of further study and subsequent write-ups, and the author will gladly accept any information from those with particular knowledge of the details that finally led to the demise of the venerable publication started by Mackay Croswell in 1792. We have come full circle now, and can no longer claim to have a paper in Catskill worthy of printing for the record on behalf of our local government. The immediate reasons for this are worthy of much speculation, and the repercussions are yet to be seen.

- Jonathan Palmer, Deputy Greene County Historian

Contact the author with questions and comments via email at: archivist@gchistory.org

Rolling Down to Old Maui - Part One

Joseph DuBois, a bank clerk from Prattsville, goes to sea in 1851 following in the footsteps of his grandfather.

Rolling down to old Maui, me boys,

rolling down to old Maui.

We’re homeward bound from the Arctic Ground,

rolling down to old Maui.

~

Azores Islands, Ship Cambria

Sept. 20th, 1851

“Dear Parents,

You may be somewhat surprised

to receive a letter from me dated at this place

but here I am on board of the ship Cambria

of New Bedford, Cotrell, Master, bound on a two

year cruise for right whales in the arctic ocean.”

-Letter of Joseph A. DuBois to his parents Samuel and Sarah DuBois.

Joseph DuBois was never destined to become the wealthy banker his father wanted him to be, and somewhere deep down his mother Sarah must have known so from the start. She had named her first born son after her father, and in so doing cursed young Joseph with the same independent streak and proclivity for adventure that had brought her father fame, fortune, and no small amount of near-misses and brushes with the varieties of death a sailor finds at sea.

Captain Allen’s spyglasses and backstaff lying on the lawn in front of the Allen House in Jefferson Heights circa 1970. Photo from the Katherine Decker Memorial Collection.

Joseph’s grandfather, Captain Joseph Allen, had retired to a stately home in Catskill before the close of the War of 1812. Catskill was a change for him, having been born on the coast of Rhode Island and brought up before the mast in the years prior to the Revolution. Like all sailors the sea was never far from Captain Allen’s thoughts, and young Joseph must have read much in his grandfather’s faraway gaze when the old man looked at the dusty spyglass and navigation instruments tucked away in the study at the Captain’s home in Jefferson Heights.

Captain Allen led a tumultuous life. His career as a merchant sailor had been put on hold by British blockades along the eastern seaboard in the 1770s when he was still a young man. Not satisfied with waiting out the English, Allen enlisted in the fledgling United States Navy and found himself serving as an Acting Lieutenant on the sloop-of-war Dolphin in the late spring of 1777. He returned to the life of a merchant sailor at the close of the American Revolution, but the late 18th century was not a time of peace on the high seas. Harried by the English and French as pawns in their great chess match of Empires, American ships were frequently attacked, impounded, or the crews impressed to bolster the ranks of the Royal Navy. This policy of impressment made the European trade difficult for Captain Allen, and he often found himself ordering unfavorable changes of course in order to run from distant sails on the horizon, lest they prove to be English warships.

Captain Joseph Allen in a portrait circa 1810. Image from the Katherine Decker Memorial Collection, made from a portrait in the collections of the Newport Historical Society.

Running from the Royal Navy was an insufferable prospect for a Patriot like Allen. His disdain for the British was fanned to flames during combat in the Revolution, and subsequent slights against American sovereignty stung Allen like personal insults. Even American triumphs in the War of 1812 were not enough quell the Captain’s prejudice towards all subjects of the Crown. In 1814 William Pullman, an English neighbor, called the Captain a liar following a business deal. In response Captain Allen (who was not an imposing figure) heaved Pullman bodily from his porch into a puddle of mud. To a judge the Captain subsequently stated “Often, when beating up the British Channel, I’ve had to douse my peak to every English vessel… Today I have doused an Englishman; peak, hull, and all!”

Such was the character of the elderly family patriarch who regaled young Joseph with stories of the high seas when the former was in his eighties and the latter an impressionable boy. Recalling the Captain’s oft-told tales given during the quiet hours of winter nights in Catskill, Sarah DuBois must have realized Joseph’s recent letter from the Azores was a natural byproduct of his upbringing.

Captain Allen’s home in Jefferson Heights and the New York State Historical Marker commemorating him. In the background is the porch from which Captain Allen launched William Pullman and claimed a final victory over England. Palmer Photo.

Samuel DuBois, Joseph’s father, was a man of unimpeachable character and of a physical stature that made men think twice before challenging him. He won the election as County Sheriff in 1846 primarily on his own merits despite being a son of one of the region’s most well-connected and deeply rooted families. He was a man who espoused force of words ahead of force of arms, and was once so incensed by the disciplinary striking of his son S. Barent by a schoolteacher that he forced the man to issue written and verbal apologies in an age when the consensus was that the rod should be applied liberally.

Samuel was a staunch Jacksonian Democrat, and as an elected official he was well acquainted and connected within the dominant political party in Greene County at that time. Zadock Pratt, the epicenter of this Democratic political vortex, was just the man that Samuel wanted his son Joseph to associate with - as opportunity came only to those young men who had good connections.

Thus young Joseph found himself in Prattsville in 1846. He was hired as a clerk in the Prattsville Bank, hunched over ledgers five or six days a week balancing the accounts and debts of a small but well-organized financial establishment. Hemmed in by the Mountains, his range of sight extended only as far as the nearest bend in the Schoharie Creek. All around him were bare hills and pastures, farms, lumberyards, and the foul smoking tanneries from which spouted all the wealth of the region. Prattsville was a stark contrast to Catskill in no uncertain terms, and Joseph no doubt soon concluded that his time in Prattsville would not extend beyond the time necessary to learn his lucrative trade.

View of Prattsville in 1844, Image via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Bookkeeping and scholarship in the 19th century brought a variety of ailments as equally detrimental to the human body as the ubiquitous hard labor that drove the economy of the age. Richard Henry Dana, Jr., a man destined to become one of America’s more influential lawyers, found his eyesight failing him following an infection while studying at Harvard in 1833. In an effort to save his eyesight Dana forewent further study, sparing his eyes the futile struggle of reading at all hours by dim candlelight, and decided to go to sea as a merchant sailor in 1834. This was an unusual decision, as it was far more commonplace for young men of his station to take a leisurely tour of Europe to broaden their horizons. Instead Dana chose a ship in the fur trade bound for California, and in 1840 his memoir of the voyage was published, titled Two Years Before The Mast.

Whether or not Joseph Allen DuBois got his hands on a copy of this rather popular book during his time in Prattsville is not known, but he doubtless heard of Dana, the bookish Harvard scholar who went to sea and returned to make a remarkable success of himself practicing Maritime Law.

Events of national significance beyond the control of the Honorable Zadock Pratt plagued his little community of Prattsville during the last years Joseph DuBois drew his pay there. The disappearance of the mighty hemlock groves that drove the tanning business was an issue Pratt had already been grappling with, and as the trees grew scarce so too did the capacity of his Prattsville tannery to generate leather at marketable quantities. Prattsville had already begun to hemorrhage workmen because of this, and many found themselves moving westward further through Delaware and Sullivan Counties and into the hills of Eastern Pennsylvania where the tanner’s work was still plentiful. Pratt himself was invested in a Pennsylvania tannery and enough other ventures that such market shifts wouldn’t effect his bottom line, but when Gold was discovered in California in January 1848 even those workmen with steady employment began to flee the mountains and their reeking tanneries for easy money in the West.

Notice in the Greene County Whig of the departure of prospectors from Prattsville for California, November 1849. Vedder Research Library Collections.

Notice in the Greene County Whig of the departure of one of the owners of Prattsville’s newspaper, the Advocate, November 1849. Vedder Research Library Collections.

Commentary in the Greene County Whig concerning the decline of Prattsville’s prospects in the wake of the California Gold Rush, while also making jabs about local Democratic losses to the Whig party. November 1849. Vedder Research Library Collections.

Joseph DuBois did not immediately abandon the mountains when news of the gold strike broke. Instead he followed a gang of Prattsville men through Sullivan County chasing tannery work, leaving the Prattsville Bank on good terms and taking his bookkeeping skills with him on the road. It is easy to imagine Joseph, his path in life suddenly laid before him, again recalling the sea stories of his late Grandfather. The life of a clerk and bookkeeper was not a game of high stakes, nor one fraught with the sorts of peril in which a young man could prove his worth. In a moment of crisis Joseph DuBois looked eastward, and without telling a soul he departed the mountains for the legendary whaling port of New Bedford in 1851 with a mind to prove himself worthy of his late Grandfather’s name.

“An old Whaler hove down for repairs near New Bedford” by Frederick Schiller Cozzens, 1882. Public Domain

- Jonathan Palmer, Deputy Greene County Historian

Banner image is “Whale Fishery - Attacking a Right Whale” by Currier and Ives, 1860. Public Domain.

The Burning of the Henry Clay

One of the most famous steamboat disasters in the history of the Hudson River claims the lives of a local family.

There is considerable poetry in the harmony of a steam engine. Within its boiler the elemental forces of fire and water are tricked into cooperation, becoming the first of humanity’s creations to liberate us from the limits of mere animal strength. The invention of the steam engine was an achievement equal to breaking the sound barrier and the creation of the internet; tangible proof that the power of the mind could be applied to cross the threshold of physical barriers once thought absolute and insurmountable.

Vertical Steam Engine from “Growth of Industrial Art” Published by the United States Patent Office, 1888

If the invention of the steam engine was equivalent to breaking the sound barrier, then the marriage of steam engines and wooden ships was something akin to the initial development of supersonic jets - the learning curve was immense and the end results were often imperfect. For millennia sailors had utilized the wind, tide, and brute strength to conquer the vastness of the sea and the power of Earth’s greatest rivers. The steamboat subverted this ancient and venerable tradition virtually overnight. These vessels dispensed with sails in lieu of mechanical contrivances and relied on fire (once the sailor’s great foe) to spurn the wind which had so reliably borne humanity to unknown reaches for generations. It is no wonder so many doubted and feared the steamboat upon its introduction, and less shocking still that the fears of many would prove well founded as steamships grew in popularity and number during the Antebellum period.

The earliest days of steam transportation on the Hudson River are recorded in graveyards. From New York to Waterford crumbling tombstones give mute testament to an industry fatally plagued by greed and hubris whose only victims were the innocent. Expedience rather than prudence governed the operation of these vessels, resulting in a steady stream of accidents that were so frequent as to almost appear comical in retrospect. Shipping companies competed neck-in-neck billing their steamboats as safer than others, while some deigned to tow their most prudent passengers in comfortable “safety barges” ostensibly beyond the range of the steamboat’s boilers in the likely advent of a mishap. Undetectable manufacturing defects in machinery, poor business practices, and the fundamental design of the ships themselves were bad enough, but all this was compounded by the desire of captains to lay claim to the title of “fastest” on the river.

Steamboat races are a subject which has been dealt with in numerous articles. The grand summary is that these races were categorically a bad idea and often downright dangerous. Captains would push their machines literally to the melting point causing timbers to buckle and boilers to fail - sometimes catastrophically. This carnage was perpetuated in the name of vanity, though some legendary captains refused invitations to race in the name of their passengers’ safety. Such was not the case when Captains Isaac Smith and John Tallman agreed to a competition between the Henry Clay and Armenia on July 28, 1852.

Three days later the Greene County Whig carried a small announcement in that week’s edition:

“The Bodies of Mr. and Mrs. Ray and their Daughter, who were drowned at the burning of the Henry Clay, passed through this village yesterday, on their way to Durham, for internment. Mr. Ray was a son-in-law of S. W. D. Cook, who was saved.” Greene County Whig, August 1, 1852 - Collections of the Vedder Research Library.

The churchyard of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Oak Hill is a place out of time. Harkening to the holy grounds of New England’s old houses of worship, gravestones here creep right to the back walls of the Church edifice. The humble aspect of the building itself belies the prominence and affluence of the community it originally served; a fact enshrined in the stately marble stones of the hallowed dead and perhaps more so in the grand homes of the neighborhood around the Church itself. Behind St. Paul’s lie lawyers, industrialists, financiers, gentleman farmers, and business owners who rode the crest of a transformative wave of industrialization in the years prior to the Civil War. These people were masters of change who embraced the most exciting and new opportunities the young republic had to offer - in a sense becoming pioneers of the Nation’s industrial frontier and harbingers of the era to come.

It is a grievous irony therefore that this same social class would end up being the victims of one of the great tragedies of their time, and that this tragedy would be brought about by the invention that typified the age. The Henry Clay and Armenia left Albany on the morning of July 28 racing neck-in-neck. These two ships were products of the same celebrated owner and builder (Thomas Collyer), a fact which only raised the stakes for the crews who knew victory or defeat would rest solely on their shoulders. Several hours into the race the Henry Clay held a comfortable lead of almost four miles over the Armenia, and such a distance could not be closed with the boats so near the finish line in New York. Just off Yonkers, as the Clay steamed towards victory, somebody on board noticed flames roaring up from the vicinity of the engine compartments. Efforts to suppress the fire were insufficient, and the fire quickly engulfed the midship. The vessel’s pilot made for shore and drove the Henry Clay at speed upon the banks of the Hudson where those near the bow could make good their escape. Unfortunately, those who found themselves trapped in the comfortable accommodations in the after section of the boat could not make their way forward to the shoreline and faced a terrifying choice between the approaching inferno and the roiling water below.

Currier Lithograph of the Burning of the Henry Clay, 1852.

Courtesy of the Hudson River Maritime Museum, Kingston, NY

The class of passengers traveling on the Henry Clay that day was of a particularly affluent nature. On board were statesmen, judges, artists, authors, and relations of the great notables of the era. Andrew Jackson Downing, one of the 19th century’s most influential architects and a pioneer in landscape architecture and horticulture, was counted among the passengers. His charred remains would not be found until several days after the accident. The flames themselves killed Downing and a number of others, but drowning would take the lion’s share of victims. The ship’s paddle wheels didn’t stop turning in time for many who had chosen to leap from the aft section into the Hudson - the engines, out of control since flames had driven the engineers from their stations, washed victims in the water away from shore out into the channel. This continued until the boilers themselves succumbed, releasing a scalding breath of steam which killed others that the Hudson and approaching flames had so far spared.

It was in the water that the Ray and Cook families of Oak Hill hedged their bet. Mrs. Cook pleaded to her husband that he escape, and probably found small comfort in knowing her grandchildren at least made it to the water. At this point there is conflict in extant accounts, but by all indications Mr. and Mrs. Cook would end up surviving the calamity only to find that their daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter met their end in the water that had seemed sure salvation from the burning wreck. In the same newspaper which carried this tale of the Cook family’s tragedy the editor of the Greene County Whig ran a statement that he was hedging bets on the Alida as contender for the fastest and most reliable boat on the River, clearly oblivious to the tastelessness of the juxtaposition.

The burning of the Henry Clay, followed by a similar and equally tragic explosion on the Reindeer that September, sparked uproar at the management of the steam passenger and freight industry on the Hudson. Similar to the calamitous sinking of the Titanic sixty years later, the people most affected by the burning of the Henry Clay were of the same social class that thought themselves impervious to such tragedies by nature of their money, influence, and importance. Indeed, these people ended up reaping the bitter harvest of their industrial speculations and business practices, and it would be but a short time after the Rays were laid to rest at St. Paul’s that reformists would call for a reassessment of the industry - the silver lining to a tragedy whose victims were celebrities and notables.

The Ray family would never know it, but the accident which claimed their lives paved the way for a golden age of steamships on the Hudson. In the face of new regulations passed by Congress and the New York State Legislature operators found themselves incapable of running their companies in a fly-by-night manner. With the practice of racing outlawed the steamship industry grew into a safe and reliable operation which offered legitimate competition with rival rail lines in the Hudson Valley for nearly another eighty years. In the end this legendary industry would simply fall victim to the same technological innovation which had brought the steamboat to the forefront a century previously, relegating the Ray family to the footnotes in a story of bygone times.

- Jonathan Palmer, Deputy Greene County Historian

Banner photo: “Black and White Photograph of the ‘Henry Clay’ by J. Bard” courtesy of the Hudson River Maritime Museum at Kingston, New York.

Musing on Spirits at the Grave of Ezra Ramsdell

A recently discovered journal lends itself to reflections on graveyards and the forgotten dead.

The graveyard is a difficult place to describe, as it (perhaps more than any other work by human hands) is vested with a power entirely divested of the sum of its parts. A description of a graveyard will always begin with paths, stones, and grass, but the description invariably transcends what can be observed with the senses. Cemeteries evoke all manner of things and awaken within us a unique philosophical and spiritual awareness. Our little corner of the Catskills is well endowed with this particular variety of muse. Three hundred graveyards of every order of magnitude dot the hills and valleys of this place, each one collectively serving as an epitaph to different, distant, and more superstitious times.

The anonymity of the graveyard is one of its startling features, with row upon row of stones bearing silent witness to a moment when the remains entombed below were the subject of not only great and immediate lamentations, but also prolonged sorrows that often endured as long as anyone remained who knew the departed in life. Gravestones are overtly a refutation of the passage of time and a symbol of our desire to endure, but in the end these weathered and crooked markers up bearing witness to a separate truth - that History is merely a reconciliation of the past with our feeble powers of memory; it is an imperfect and weighted truce at best.

This was a subject of no small significance to Augusta Hallock, a girl only eighteen years old when her friend and neighbor Ezra Ramsdell passed at the age of twenty-five. In a composition book she kept while attending Greenville Academy she devoted two separate entries to the occasion of his passing. The themes she confronts are universal, and Ezra’s passing was something she took several months to process on the pages of her journal. Below is a poem she wrote following a visit to his month-old grave:

Page one of “Lines on a Bouquet taken from the Grave of Ezra Ramsdell” by Augusta Hallock, 1854

Page two of “Lines on a Bouquet taken from the Grave of Ezra Ramsdell” by Augusta Hallock, 1854

Ezra Ramsdell’s grave is what you may expect of someone who left no descendants to mourn him nor great achievements to enshrine him in the pages of history. Ezra instead was a young man who once had occasion to pick flowers for a girl who lived down the road. On a Sunday afternoon in July 1854 that girl wrote:

“Many brightfully woven dreams of the future have faded. Many joyful anticipations have been crushed and tears, blinding tears fill eyes which would have beamed with hope and joy… How false and fleeting are all things here. The fairest and brightest of Earth’s treasures pass away leaving nothing but the remembrance of the past.”

Her passage leaves much to be inferred about her relationship with Ezra, and contemplation on her lines lends a somber cast to the already humble aspect of his grave.

1854 proved particularly tragic, and Augusta’s journal would end up containing passages on three young neighbors of hers who died of fever that year: Elliot Ackley who passed in May at the age of twenty-six, Ezra Ramsdell who died in June, and Isaac Gordon who passed that August at the age of nineteen. All three men rest in the same row in the old section of Locust Grove Cemetery just west of the hamlet of Greenville. They are joined by ten other neighbors and peers throughout the cemetery under the age of fifty who died that same Summer, ostensibly all were victims of yellow fever, smallpox or typhus. In light of such a horrible occurrence it is obvious why death was on Augusta Hallock’s mind during those months, though one wonders whether Augusta ever meant for her journal to serve as a separate epitaph for these three young men. Her passages grapple with the unfairness of their deaths, and what trivial anecdotes appear within that shed light on their characters are minimal and unintended.

The grave of Elliott Ackley.

The grave of Ezra Ramsdell.

The grave of Isaac Gordon.

Whether ghosts exist or not is a debate best left to campfire raconteurs, though historians and archivists are also uniquely qualified to take a crack at an answer. Consider for a moment when the last time was that the name of Ezra Ramsdell was spoken aloud or even privately contemplated by a living soul. Sure, the graveyard sexton most certainly saw his name on the stone, and passerby probably remarked on it at various times, but it takes something more than letters on a rock to resurrect a memory. This is where the archive becomes the tool of the alchemist.

The Journal of Augusta Hallock resides in a tomb of its own, shelved amongst the last vestiges of a legion of our forebears who by a roll of Fate’s die reside on a strange separate plane of existence where they remain gone but not forgotten for the foreseeable future. Their hopes and dreams are perpetuated beyond their earthly departure by the preservation of the trappings of their lives: letters, diaries, wills, the prize ribbon from the fair, all manner of things which substantiate the existence of someone otherwise relegated to the anonymity of the burial ground. This is why archives tend to be so loud. Even after hours, when only the staff is there quietly working, the shelves howl with the voices of those once possessed of lives as vibrant as any living person.

In the archive, consultation with the dead is as simple as taking a box from the shelf and letting those within bare their great sorrows and joys. Therein lies the power of a manuscript collection: in those boxes of papers S. Barent DuBois attends the deathbed of a dear friend, Mary Stone laughs at a joke by Winslow Homer, Black Thomas toils in a farm field he will never own, Peter Brandow buys a piano, and Ezra Ramsdell picks flowers for a girl from Norton Hill. These vignettes, framed so vibrantly despite the passage of centuries, transcend the grave in their quest to be recalled.

by Jonathan Palmer, Deputy Greene County Historian

The Oldest Photograph of Catskill

An Ambrotype of Catskill proves to be the oldest photo of the village and the earliest surviving image of the church designed by Thomas Cole.

In September of 2016 Barbara S. Rivette donated a curious photograph to the Vedder Library as a supplemental accession to her extensive collection. Mrs. Rivette hails originally from Catskill and is the daughter of Mabel Parker Smith, the late Greene County Historian who preceded Raymond Beecher. The photo Mrs. Rivette donated turned out to be an exceedingly curious artifact, and may prove to be one of the earliest surviving landscape photos of any location in Greene County.

Lets backtrack briefly to cover some previously trod ground. In 2018 an advertisement was found in a back issue of the Catskill Messenger from 1842 that announced the arrival of a photographer in Catskill. This traveling photographer stated he would be selling equipment and doing demonstrations of the Daguerrotype Process for the public at Van Bergen’s Hotel (probably in the vicinity of the modern Court House on Main Street). The Daguerreotype process was extremely new at that point, having been invented less than two years before as the first ever viable photographic technique. Daguerrotypes used polished metal treated with a chemical emulsion to literally burn a positive monochrome copy of the subject onto the treated plate for posterity. It was a time consuming process that required a studio setting to be properly executed. The photographer demonstrating this process in Catskill in 1842 was likely the first ever photographer to visit and ply his trade in this County, though he would soon be followed by a slew of local practitioners.

The Daguerrotype was refined over the ensuing decade before it was finally superseded by an alternative process: this being the somewhat more elegant Ambrotype. A variation of the wet collodion process, the Ambrotype had a shorter “day in the sun” and remained in common use only through the Civil War before being entirely replaced by the cheaper tintype. Using a treated emulsion on glass instead of silver, the Ambrotype was still a difficult process to take beyond the confines of the Studio setting because the delicate plate had to be exposed while the chemical emulsion was still wet. An exposed Ambrotype created what is more or less a positive image on a delicate sheet of glass, and the positive would then be mounted within a wood and velvet case for its protection. Naturally portraits make up the majority of compositions found on remaining examples of Ambrotypes, though an experienced photographer was capable of taking a landscape under the right circumstances.

Here is the Ambrotype donated by Mrs. Rivette:

The central building is the obvious subject of the photo, that building being an extremely early Ice House in the process of being filled by workmen. The most notable feature of the Ice House is the scaffolding structure across the front of it, which likely served the function of allowing workmen to slide blocks of ice along the length of the building once a conveyor belt hauled the blocks to the desired tier of the storage space. This type of design would become increasingly uncommon later in the 19th century. The other oddity on this building is the flag flying on it. The 28-star flag of the United States was official for only one year between 1846 and 1847 during the presidency of James Polk. It commemorated the addition of Texas to the Union and was quickly superseded following the admission of Iowa the following year. The fact that this flag is shown flying over the Ice House does little to help us date the image, as the Ambrotype process was not yet invented when this flag was the official US Flag in common use. It is far more likely that this scene dates between 1855 and 1860, and that the owner of the Ice House was flying an older flag which was too large to bother replacing right away.

Immediately to the right of the Ice House is the foundry of Benjamin Wiltse, which was established in 1808 and purchased by Benjamin Wiltse and his brother in 1839 when they moved to Catskill from Columbia County. This foundry produced cast metal goods of a primarily industrial nature and will hopefully be the subject of a later article. Fortunately for us this building also still stands virtually unchanged from its early 19th-century configuration and allows us to orient the photo almost exactly despite the passage of over 150 years.

Assisting us with the orientation of the photo are two of Catskill’s earliest brick blocks, one of which also still stands. These early brick blocks on Main Street date more or less to the 1820s, and the remaining one is the building which currently hosts an H&R Block on its lower end and the offices of the Management Advisory Group of New York at the upper end. Some of you might also recall this same old brick building as the home of DuBois’ Drug Store. That building is the one directly above the roofline of the Wiltse Foundry in the Ambrotype.

The figure below is an approximation of the position of the photographer based on the angle of the buildings and field of view. It is possible that the photographer was standing on the surface of the frozen Catskill Creek, but far more likely he was on the opposite shore (possibly even taking this photo from the lower floor of a building based on what is at “eye level” in the scene). Not knowing the focal length of the camera lens also makes determining their exact location difficult.

The most significant building in the photo, unfortunately out of focus, is the second iteration of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. This building, which stood on Church Street, replaced an episcopal church which had burned in 1839. A call was put out by the vestry in 1840 for design proposals for a new church to replace it, and Thomas Cole (a member of the design selection committee) was the creator of the winning proposal. Cole’s gothic church edifice was one of an exceedingly small number of architectural designs the artist ever realized in brick and mortar, though its exact appearance during his lifetime was never previously corroborated by any renditions or photographs other than Cole’s original design proposal.

To clarify: other photographs of this particular St. Luke’s Episcopal do exist from the 1890s, but all of them show what appears to be Cole’s original design with a tastefully added bell tower also in the Gothic style. What Cole’s original drawing tells us is that HE never intended a bell tower on the church. This put the photographic evidence at odds with the original plan. With the discovery of this Ambrotype we now have proof that for at least twenty years the second St. Luke’s appeared exactly as the artist had intended, and this is notable for helping to contextualize “Thomas Cole the aspiring architect” and “Thomas Cole the practicing architect.”

What became of all these buildings? To the best of our knowledge the structures in the background succumb to fire and demolition, as many of the residential homes do not seem to match current buildings in those neighborhoods. One of the old brick blocks was destroyed what must have only been a few years after this photo was taken and replaced by a block of reconstruction-era businesses of three and four stories in a more contemporary architectural style. The Ice House that made up the front and center of this photograph was long gone by the 1880s and replaced by a coal yard which apparently used the empty lot for storage. Whether that building burned or was removed will only be determined through further research.

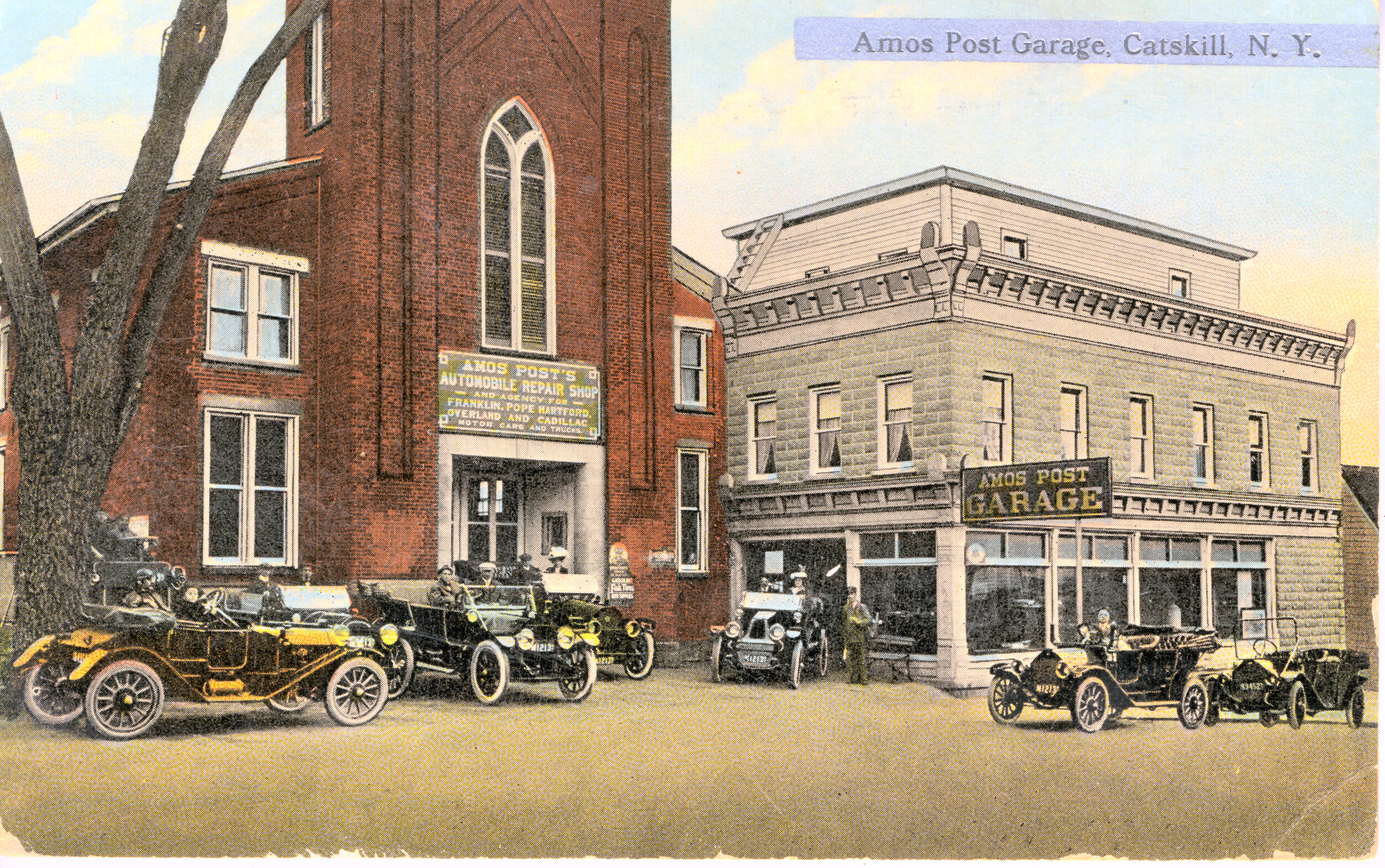

St. Lukes fell to the wrecking ball far more recently. In 1896 Cole’s church was abandoned and replaced by the third iteration of St. Luke’s Episcopal on the hill between Bridge and Williams Streets. Cole’s Church, suddenly empty, soon became the garage of Amos Post, changing hands a few more times before being utilized as the offices of the Daily Mail. When the new County government building was constructed Cole’s mostly forgotten 1841 gothic church was finally demolished to make way for a parking lot, and now “Church Street” is the only reminder we have of where this building once stood.

By Jonathan Palmer, Deputy Greene County Historian

Aftermath of an August Storm

A freak storm brings down a plane on an August night in Coxsackie.

In the late afternoon of August 10, 1936 a storm of unusual intensity roared its way eastward over the Catskills in the fashion of nearly all weather in this region. For half an hour much of Greene County was blasted with exceedingly heavy rain, making it necessary for most households to switch their lights on early as the sky darkened and the temperature dropped nearly ten degrees. The thirty-minute deluge gave way to a howling wind which bent trees and tore at the shingles of homes and barns throughout the afternoon and evening. Unceasing lightning, intermittent hail, and waves of rain continued into the night “doing much for vegetation” in the practical coverage the Catskill Recorder provided farmers four days later.

By all indications Greene County residents had avoided disaster at the hands of this surprise storm. No barns had fallen, toppled trees were to be cut and seasoned for firewood, and crops across the county sprang to life despite what had otherwise been a hot and dry summer. The lightning had surprisingly caused no lasting harm, though it had tried its best to kill bank cashier Harry Emens in Cairo when a bolt struck nearby telephone wires while he was making a call. Likewise shocked but unharmed were twenty-five men at the County Farm who were nearly electrocuted when lightning hit a tree they were taking shelter near. Foreman William Dyce, who was the most seriously harmed, recovered his senses in a day and went back to work. All was not well however at the Swartout Farm, which lay on the road between Athens and Coxsackie. The morning of August 11 saw a line of police vehicles departing after what had been an unusually tragic and eventful night. Off in the Swartout’s field freshly turned soil spread across a thousand yards revealed bits of shattered wood, canvas, and mangled mechanical contrivances which a mere twelve hours before had been a symphony of engines and airframe en route from Long Island to Albany. Tattered fragments of newspaper lay sodden in the mud.

The business of getting printed news distributed fast and efficiently was an undertaking of monumental proportions in an age before interstate highways and overnight shipping. The newspaper empire of William Randolph Hearst, which printed papers in New York City, had a readership and distribution which extended across the northeast. Outdated news would not suit readers of Hearst newspapers, so the latest and fastest modes were employed to get the news where it needed to be. Notably, to get copies of the New York Mirror and New York American to Albany, Hearst employed aircraft which could make the run in roughly three hours from the metropolitan area to the state Capital. That was fast, even for the most discerning subscribers of those papers.

Hearst Newspapers’ planes of choice were manufactured by Sikorsky Aircraft. A tested and reliable company, Sikorsky had already left a considerable mark in the short history of aviation with their remarkable designs. Of particular note were their S-38 and S-39 Models, twin and single engine variants of a durable and utilitarian amphibious plane noted for being able to land and take off from either land or water carrying considerable cargo or several paying passengers. These planes were flown successfully from locations around the globe, and were commonly found ferrying passengers between islands in the balmy Caribbean. Several adventurers and explorers had even flown these variants over the uncharted jungles of South America and across the vastness of Africa, making discoveries and filling in blank spots on the map as they went. Apparently these Sikorsky amphibians could also be spotted over Greene County as they flew back and forth weekly making newspaper deliveries to Albany.

US Army Air Force Photo of a Civil Air Patrol S-39 similar to the plane that crashed in Coxsackie.

It is likely that the wreckage on the Swartout Farm had once been an S-39. The Recorder’s reporter, in gruesome detail, noted: “The engine was in an open field, 2,000 feet north one wing was found and about 1,000 feet to the east, the other wing was resting. The tail was about 1,000 feet from the plane and the pontoons were almost the same distance away.” The remnants of the cockpit were elsewhere. The Swartouts had heard the plane come down at about 9:40 that evening. The S-39, with a cruising speed of 95 miles per hour, would have remained on schedule to reach Albany at 10 that evening were it not for the intensity of the storm.

William Howell, seated at left, radios from his plane that the Hindenburg had just been spotted off the coast of the United States on its maiden flight from Europe. Photo from the August 11th, 1936 edition of the Long Island Daily Press.

William P. Howell, 36 years old, was a veteran pilot familiar with his plane. Born three years before the Wright Brothers flew at Kittyhawk, Howell was a member of a generation of young men and women who felt called to the new and dangerous frontier of manned flight. He had joined the ranks of professional civilian aviators fifteen years prior, probably cutting his teeth behind the controls of a surplus plane from the First World War. Howell was flying before parachutes were a common safety feature, a notion that upped the stakes and excitement for many aviation pioneers, but a fact that also made the profession exceptionally unforgiving. In his fifteen years among the clouds Howell had already made a name for himself as one of the pilots who flew out to meet the Hindenburg over the Atlantic when it arrived on the coast of the United States on its maiden voyage. Likewise he had ferried photographers out to document the arrival of the Normandie and Queen Mary, superstars of the fashionable transatlantic passenger lines, on their first arrivals in New York Harbor. Testifying to his value as a veteran pilot, William Howell was being paid $150.00 a week to fly newspapers up the Hudson Valley in August 1936.

Lewis Burnell was the second half of the two-man team necessary to keep a Sikorsky S-39 aloft. Unlike motorists at the wheel of automobiles of that era, pilots did not have the luxury of being able to pull over to the roadside when mechanical issues arose in their planes. The flight mechanic, who put his life in the hands of a skilled pilot, likewise held the life of the pilot in his hands as he kept an eye on the humming radial engine, control surfaces, and straining cables that kept their plane in the clouds. It may be said the only person more possessive of an aircraft than the pilot flying it is the mechanic who keeps it running, and Mr. Burnell was no exception. Unfortunately for William Howell and Lewis Burnell there was little they could do about the weather, and their schedule needed to be kept lest they disrupt the intricate system that got news delivered on-time.

Page one of Lewis Burnell’s entry in the register of the W. C. Brady’s Sons Funeral Home. Vedder Research Library Collections.

In the steady hand of County Coroner William E. Brady the names of Lewis Burnell and William Howell were added to the grim register of William C. Brady’s Sons Funeral Home. The Swartouts had phoned for help minutes after they discovered the plane’s wreckage, summoning Sergeant Conway of the State Police from Catskill along with Coroners Brady and Atkinson and members of the County Sheriff’s Department. Both pilot and mechanic were found at their stations in the crumpled cockpit of the plane, their bodies bearing the marks of an instantaneous death delivered by a high-speed impact.

William Brady was a dignified and amicable man, a demeanor he inherited from his father and fellow Funeral Director William C. Brady. A veteran of the First World War and longtime business partner with his father in their funeral home, Mr. Brady was accustomed to death in all its forms. When his best friend and fellow veteran Louis Tremmel passed away unexpectedly William had taken in Louis’ children and raised them as his own, a final gesture to his friend and comrade. Now, in the capacity of Coroner, Mr. Brady was an attendant to the passing of both friends and strangers alike across much of Athens, Coxsackie, and New Baltimore. Despite his admittedly grim resume, the wreck he arrived to examine on the Swartout farm was one of a most unusual nature, and may have been the only plane crash he ever reported to during his long career. William Brady’s stepson Bill Tremmel had no idea where his stepfather was going when Mr. Brady left the house at 10 that night. Yet even at his young age Bill was already accustomed to the difficult hours and responsibilities of his stepfather’s line of work.

Louis Tremmel and William E. Brady in their uniforms during the First World War.

The scene on the Swartout Farm became increasingly chaotic as the night wore on and the rain fell. After the crash had been surveyed the State Police and Sheriff’s Department immediately set about dispersing souvenir hunters who had arrived to scrounge bits of wreckage. About an hour after the crash William Howell’s wife arrived in a car, having driven herself from Albany Airport where she had been awaiting the overdue plane. Consumed with grief, her presence and the subsequent arrival of Howell’s father dampened the spirits of all in attendance as they gathered remains and made notes to prepare for the inevitable investigation. It was not an easy night, and the Recorder’s reporter took pains to relate the theatrically tragic course of events as they unfolded.

A day later in the morgue of his funeral parlor Mr. Brady made the necessary preparations to return the remains of William Howell and Louis Burnell to their homes on Long Island. Everything was paid for by Thomas J. Reynolds, an editor for the New York American. Two embalmed bodies totaled sixty dollars, transporting each by Auto Hearse to East Elmwood, New York was one hundred dollars, and several long-distance telephone calls added an extra six dollars and eighty cents to the bill. Mr. Brady noted that the funeral records were made in triplicate, necessary for such an unusual case, and within four days the entire account was settled and done. All that remained were muddy ruts in the Swartout’s field where trucks had hauled away the wreckage and permanent damage to two trees that had been clipped by the plane on its descent.

We dug this story up eighty-three years later because of an odd happenstance. It seems the State Police and Sheriff’s Department had their hands full on the night of August 10, 1936. So full, in fact, that one of the souvenir hunters that showed up to scrounge a piece of the plane indeed made off with a coveted fragment. While attention was focused elsewhere, someone managed to cut a perfect strip of canvas from the crumpled tail section of Howell and Brunnell’s S-39 as it lay in the mud one hundred yards from the nearest section of the wreck. The unnamed looter cut the fragment into a pennant and detailed the silver-painted canvas with a black border and remarkable rendition of a Sikorsky S-38. On the back, written with a typewriter, were dates and details about the origin of this strange fragment of fabric. Were it not for the kind donation of this grisly souvenir, it is likely this event would have remained quietly forgotten.

By Jonathan Palmer, Deputy Greene County Historian.

(A version of this article originally appeared in the June 4th and 11th 2019 issues of the Catskill Daily Mail.)

Fragment of the tail fabric of the crashed S-39 at Coxsackie, collections of the Vedder Research Library courtesy of a donation by Linda Deubert.

Photography Comes to Greene County

An advertisement is rediscovered in the Catskill Messenger heralding the arrival of the first photographer to Greene County in 1842.

It would be difficult to imagine a time when it was impossible for the average person to snap a simple picture as they went about their day. Cameras are in our cell phones, on our computers, even in the tailgates and dashboards of our cars. It is a matter of routine to brandish our cell phones and capture a photo of a funny moment, amazing sunset, or family gathering - not to mention the added ability to instantly send that photo to friends and family virtually anywhere around the globe. We now take this advancement for granted, but photography as an invention, activity, and profession is really quite a recent phenomenon. So recent, in fact, that we can name the exact date that photography was introduced to this county.

This all stared while I was browsing a run of the Catskill Messenger from 1841-1842 looking for the date that the paper first switched publishers. In those days newspapers were founded to support certain political parties, and several thousand Whigs in Greene County had only the Messenger to convey them news and editorials on the Whig party’s successes (and more frequent failures). The speeches of their Whig champion in Congress, Henry Clay, appeared so frequently that he could almost be considered a regular columnist.

For ten years Greene County Whigs who read the Messenger had counted on the steadfast commentary of Ira Dubois, sometimes Sheriff and storekeeper in Catskill who founded the Messenger in ’31. His stepping down from ownership of the paper he started was a big deal. In May of 1841 it turns out that Ira was elected to a municipal office, and he sold his cherished Messenger to friend and fellow Whig William Bryan for an undisclosed sum. Because it was the only local Whig paper, ownership of the well-established Messenger was quite lucrative for Bryan. Shouldering his responsibility gratefully, Bryan made sure he kept printing the news Whig readers wanted: science, arts, market, and international news filled its pages through 1841 and ’42.

It was here in an April 1842 issue that I found a fascinating advertisement. The headline read “Daguerrotype Miniatures taken by A. Johns” and named the place and times he could be found in Van Bergen’s Hotel on Main Street in Catskill. Daguerrotype photography was extremely new at that time - in fact it was the first practical photographic method used on a wide scale, and it had made its debut in Europe in 1839 with much fanfare. The process was far from perfect, and other inventors eager to make their mark continued to improve the process through the 1840s, ‘50s, and ‘60s before it was superseded by simpler techniques.

The daguerrotype process, like many early photographic techniques, required long exposures and bulky equipment. This made daguerrotype photography suitable almost exclusively for studio settings where subjects could be posed and photographed in controlled lighting. These early cameras didn’t use celluloid film to create a negative exposure. Instead the photographer, using a bit of knowledge of chemistry, would coat a polished metal plate with chemicals that would cause the image to be “burned” onto the metal when it was exposed to light inside the camera. This meant every daguerrotype was one-of-a-kind and that making multiple identical copies was not possible. “Developing” the image occurred immediately after a treated metal plate had been exposed to light, so having a darkroom nearby was a necessity. Holding the exposed plate over a heat source “fixed” the developed image permanently on the metal substrate.

This complicated process involving light and mysterious chemicals seemed to be science fiction, making it a big deal that a photographer was showing off a camera in Catskill less than two years after photography had been introduced to the world. We do not know how A. Johns’ visit was received or who took him up on the offer to purchase cameras of their own, but we know that from this point onwards photography was here to stay.

By Jonathan Palmer, Deputy Greene County Historian.

(A version of this article originally appeared in the November 27, 2018 issue of the Catskill Daily Mail.)

![The grave of William, Abbe Ann, and Caroline Ray who were all killed in the burning of the Henry Clay on July 28, 1852. Buried at St. Paul’s cemetery, Oak Hill, Durham Township. [Palmer Photo]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59d3dc3ae9bfdfba3b1b9958/1572983516471-0M5K49GSVICMPPBDQ4SX/_DSF0260.JPG)