The Wreck of the Swallow

On the snowy evening of April 7, 1845 the steamboat SWALLOW departed her dock at Albany loaded with approximately 250 passengers bound overnight for the City of New York. Fashionable and fast, the SWALLOW offered businesspeople and time-conscious travelers one of the fastest and most comfortable conveyances between the capital of New York State and its unofficial business capital at New York City. The evening route was intended to leave passengers rested and ready the next morning to conduct business at their respective destinations. None knew the journey would end a short two hours later in a cataclysm of shattered timbers, fire, and water — a tragedy summoned by a culture of heedless profiteering endemic to the operation of the steamboats of that age.

The SWALLOW was owned jointly by “The People’s Line of Steamboats on the North River” and “The Troy and New York Steamboat Association.” Daily operations were orchestrated by the Association, a profit-minded assembly of investors including approximately one hundred shareholders with a board of five trustees and three directors. Naturally, much of the decision making behind the operation of the SWALLOW emphasized publicity and revenue over passenger safety.

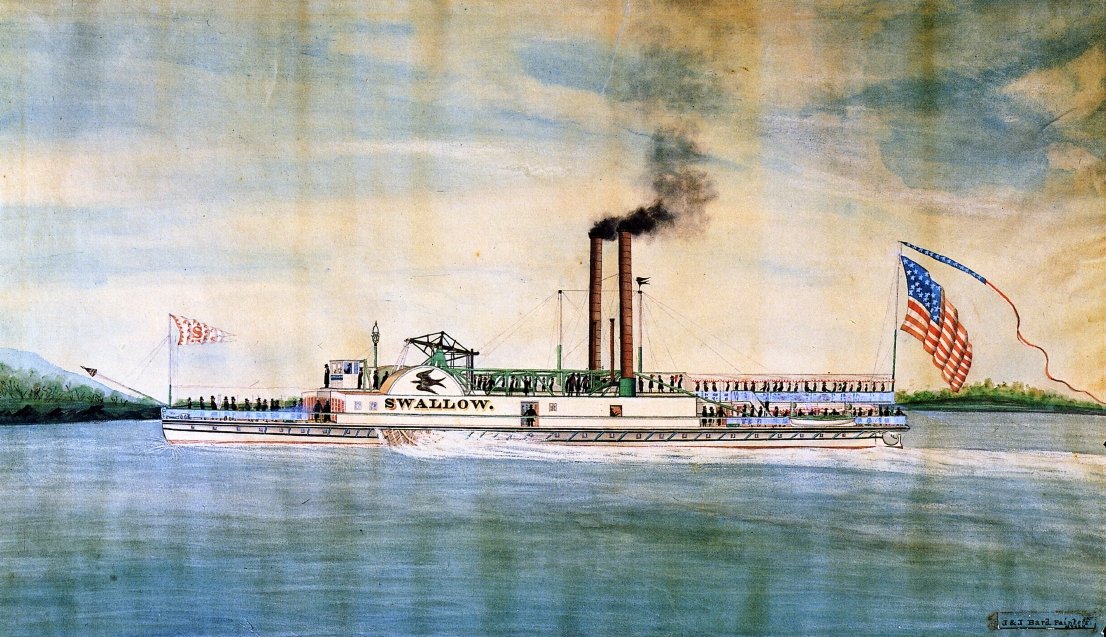

The Steamboat SWALLOW as she appeared around the time of her commissioning as a day boat in 1836. Painting by celebrated maritime artists James Bard (1815-1897) and John Bard (1815-1856), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Swallow_(steamboat_1836)_by_Bard_Bros.jpg

The speed of the SWALLOW, like many of her contemporaries, was an important selling point and a subject of pride among her stakeholders and management. Following a refit at the end of the 1844 season it was held that the SWALLOW could make upwards of seventeen miles per hour as her top speed — quite fast for that time. This was known because she and competitor steamboats frequently undertook unofficial races which jeopardized the safety of boatloads of paying customers in the name of attracting more passengers to a winning boat on a subsequent trip. By the mid-1840s such races were technically illegal, but no system existed to identify and address those who continued the practice.

While winning steamboats certainly made the headlines in regional papers with regularity, so too did news of the alarmingly frequent disasters that befell boats which were pushed too hard. Boiler explosions, fires, groundings, and collisions appeared in the news just as often as headlines concerning triumphs and broken speed records. The potential for disaster was compounded by flaws in the way steamboat officers were selected. As one example of this systemic problem the pilot of the SWALLOW, William Burnett, was previously “addicted to the use of ardent spirits” though he claimed to have had only one beer while on board the vessel that fateful night. This same pilot had run the SWALLOW aground twice in the past and once sank a sloop in a collision. All of this culminated in his previous dismissal from the post for negligence. His subsequent reappointment prior to the disaster illustrates just how flawed the corporate culture was that would place a man in a role they were demonstrably ill suited for.

In the same Senate report that describes pilot Burnett’s previous struggles with alcoholism and sloops appears a scathing indictment of the entire command structure common among Hudson River Steamboats at that time. The Captain, contrary to every obvious principle concerning the management of a ship, did not have clear authority over the Pilot and Engineer, effectively rendering him a figurehead with more responsibility over the management of passengers than the actual navigation and operation of the vessel. Indeed the tradition of Ships Pursers being elevated to the position of Captain among Hudson River Steamboats endured long after the SWALLOW met its end. With no single experienced person clearly in command there was no possibility of sound judgement ruling difficult or dangerous situations. Then again, it shouldn’t have been a grand question as to whether running at speed was a prudent idea on a dark snowy night.

This fatally flawed command structure, paired with a desire among stakeholders and crew alike for speed, had already doomed the SWALLOW as she rushed southward through the night. The SWALLOW rapidly outpaced the ROCHESTER and EXPRESS, fellow night boats which had left Albany at the same time, and likely made an average of fourteen miles per hour the entirety of the distance between Albany and a rocky outcropping called Dooper’s Island along the shoreline at Athens, New York. Around eight in the evening residents of Athens and Hudson alike were woken by a crash heard at least a mile in all directions. Within moments those near the banks of the River in Athens observed the glow of flames that briefly illuminated the silhouette of a steamship, its bow driven over thirty feet into the air upon a rock and quickly sinking by the stern. Passengers poured out onto the decks, many chancing the water to make distance from the wreck lest it continue to burn. The stern sank within five minutes, extinguishing the boilers and nascent fire and plunging all into darkness.

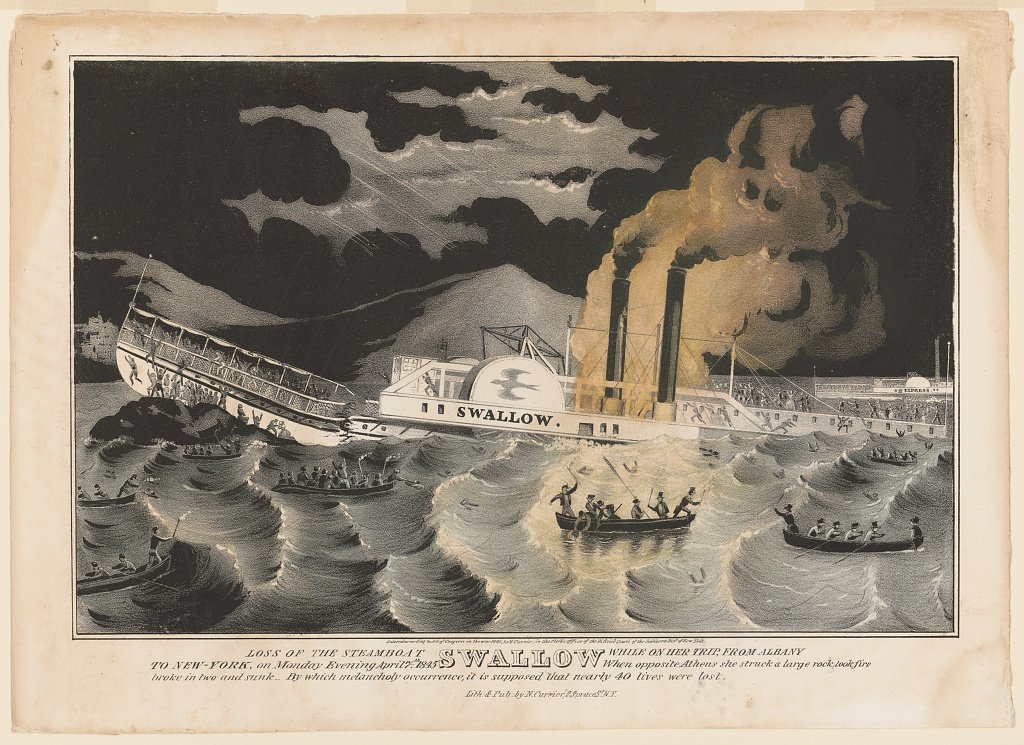

Loss of the steamboat Swallow while on her trip from Albany to New-York, 1845. New York: Published by N. Currier. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002709958/.

Confusion dominated in all quarters from the moment the SWALLOW ran aground and sank. In the common custom of the time no clear accounting of the total number of passengers was ever taken, so it remained (and still remains) uncertain what the exact death toll was. Newspapers throughout the valley began publishing accounts within a day of the sinking, and it was claimed by some that upwards of forty persons died, though only thirteen bodies and one missing child could be identified by the end of the month. The hour of the sinking, the subsequent destruction of the aft staterooms by river currents, and the removal of survivors by the ROCHESTER and EXPRESS as well as good samaritans in Athens meant it was unclear for a time exactly who survived and where they ended up.

Conflicting stories as to the circumstances that precipitated the disaster filled newspapers in the ensuing weeks. These ranged from inclement weather, to racing on the part of the steamboats running that night, and even simple base negligence by the pilot and captain. A select committee charged with investigating the disaster on behalf of the New York State Senate began collecting salient facts within days of the sinking, including detailed measurements of the situation of the wreck and its relationship with the shoreline.

Pilot William Burnett gave testimony certain to cast himself in a prudent light, stating that after coming past Four Mile Point he slowed the SWALLOW to approximately seven miles per hour and proceeded with caution. This testimony conflicted with his additional assertions that he had fine visibility and knew his position relative to the Athens shoreline moments before the collision. Ultimately he blamed a strong crosswind for blowing the SWALLOW off course within about six hundred feet of the rock. The written reply of the select committee, after introducing the pilot’s narrative, read thus:

“The committee cannot reconcile this story with the facts.”

The select committee chalked up Burnett’s testimony as predominantly nonsense, and rightly so. The SWALLOW covered the roughly 27 miles from Albany in two hours. Simple arithmetic gives us an average of almost fourteen miles per hour being necessary to accomplish that. Accounting for the points in the journey when the pilot gave an account of his speed as being half that or less (including the departure from Albany and his oddly prudent pass through the Athens channel) this means the SWALLOW would have had to exceed its top speed elsewhere at other dangerous points in the channel coming south from Albany.

That Burnett’s testimony was riddled with falsehoods is corroborated by several facts uncovered by the select committee. The absurd position of the wreck, which couldn’t have arrived so high upon the rock unless it had been moving at a tremendous rate, illustrated clearly the speed and force of the impact. Some passengers submitted a subsequent resolution defending the pilot’s testimony, but others found fault in it and the question remains whether passengers enjoying the evening in comfortable aft staterooms could have had a clear sense of the Ship’s speed in the dark.

Likewise, the committee found it irregular that any pilot would have decided to slow their vessel at a position where the channel became so clear and defined. It was in fact highly unusual among pilots to slow their speed at Athens and the report elaborates on this point at length. Indeed, even Burnett said he could see his location well despite the weather. Lastly, none except the pilot claimed to have observed any wind that could have acted with such force to cast the SWALLOW off course in such a short distance.

Detail of a map prepared by the select committee showing the position of the wreck in mid-April of 1845.

The SWALLOW came to rest upon the rock more or less at coordinates 42.263750, -73.804724. This location is now part of the shoreline at Athens situated immediately north of the the Village’s sewage treatment plant. Where it had once been known by several names depending on the source, the sinking thereafter earned the island the moniker “Swallow Rock.” The rock endured at least into the 1870s, at which point encroaching fill for an ice house finally covered it up, but local writers were able to refer to the location with certainty into the 20th century.

This is not to say that the sinking of the SWALLOW didn’t endure in collective memory. Generations of Athenians were regaled by tales of the disaster, and debate as to the causes of the wreck have captured the imaginations of countless writers and historians. In a way this was the only lasting result of the tragedy. The wreck of the SWALLOW was removed and hauled away about a month after the sinking - its timbers famously salvaged for a house in Valatie, the running gear repurposed, and its dead buried. William Burnett was put on trial for manslaughter but acquitted, and the night boats kept running as before.

The select committee’s report was submitted to the senate at the end of April while salvage operations were underway at Athens. It conveyed the nascent awareness of a nation becoming increasingly sensitive to the mounting evidence of an industry running roughshod over the best interests of the traveling public. There was undoubtedly some appeal in a slow boat where passengers survived over a fast one which perpetrated the occasional massacre, and it didn’t take men of vision to see that regulation must reign where decency would not.

In calling for new safety regulations, the committee members included in their conclusions a passage from Emer de Vattel’s The Law of Nations: “If a nation is obliged to preserve itself, it is no less obliged carefully to preserve all its members.” It would take almost a decade and two more horrifying accidents on board the HENRY CLAY and the REINDEER (standouts in a slew of more minor incidents) to bring about the regulation necessary to improve the safety of steam transportation on the Hudson River.

By Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian. Questions and comments can be directed to Jon via archivist@gchistory.org

Additional Reading:

Senate Document no. 102 submitted by the Select Committee appointed to investigate the cause and circumstances of the late disaster of the steamboat Swallow, on the Hudson River, April 26, 1845.

Captain William Benson’s relation of the tale of the disaster, courtesy of the Hudson River Maritime Museum.

Andrew Amelinckx’ version of the tale as published on Hudson River Zeitgeist.