French Émigrés and the Plan of Esperanza

In the tumultuous years following the commencement of the French Revolution in 1789 the United States played host to a rotating menagerie of representatives, expatriates, and refugees from the young French Republic. The influential Livingston family, representing the epicenter of society and politics in New York, accepted several stateless Frenchmen into their graces in the early 1790s - chief among them surveyor/architect Pierre Pharoux, visionary Pierre de la Bigarre (aka Peter DeLabigarre), and artist Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin.

These three men, acquainted as countrymen in a foreign land and involved in overlapping ventures, are celebrated by modern scholars for a number of different and notable achievements. Despite the esteem with which they are held in academia, their influence is often overlooked or entirely unknown in the upper Hudson Valley where these men spent considerable time. This is surprising given that these French émigrés were integral to the story of Esperanza, the 1794 land speculation undertaken by Edward Livingston, John R. Livingston, Ephraim Hart, Elihu C. Goodrich, and Brockholst Livingston to create a new planned city where the Village of Athens now stands.

How these Frenchmen managed to remain omitted for so long from the history of Athens is a complicated tale, but matters were made worse by William Pelletreau. It appears that Mr. Pelletreau, who wrote the remarkable and authoritative chapter on Athens for the 1884 History of Greene County, made a surprising transcription error from an early map. That map, engraved circa 1795 showing the proposed city of Esperanza, was a fascinating artifact complete with street names and designated civic spaces. The copy Pelletreau examined was likely one of two copies which were accessible to him in the 1880s. Neither local version of the Plan of Esperanza included a title nor attribution naming the creator, though tradition brought down to him tale that the map was produced by a mysterious “P. Pharmix.” That name, as it turns out, was a misconstrued reimagining of the surname Pharoux, though this connection has only been definitively proven by scholars in the last thirty years.

This is Greene County’s record copy of the Plan of Esperanza. The map’s legend does not include an attribution naming Pharoux, nor does it bear the cryptic name “Pharmix” which William Pelletreau attributed as the map’s creator. The map is glued into Map Book One, and there may be obscured writing on the map which can no longer be read. It is very likely this local copy may have been the one Pelletreau used as a reference when writing his chapter on Athens in Beers’ History of Greene County.

Unknown, from Pierre Pharoux. A Map of the New City of Esperanza. Scale not given. Hudson Valley, c. 1795. Image scan courtesy of Greene County Real Property Tax Services and the Greene County Clerk’s Office.

Pierre Pharoux is the most tragic of the three émigrés involved in the Esperanza speculation. Originally from Paris and a participant in the earliest years of the French Revolution, Pharoux is celebrated today for the journal he kept of his time in America and for several unusual civic and architectural plans he produced for affluent clients in the Hudson Valley. He originally came to the United States as one of the surveyor-agents working on behalf of the La Compagnie de New York which was organized to settle refugees of the French Revolution on land in modern-day Lewis and Jefferson Counties. Pharoux’s journal offers scholars detailed insight on his projects and the social circles he moved in during his time in the United States, but his work was cut short when he drowned in a rapids with several others in September of 1795.

It is likely Pharoux’s death, the unrelated failure of the Esperanza venture, and the misattribution of the map he helped create conspired to obscure his contributions for so long. Fortunately recent attention given to an auctioned engraving of his Plan of Esperanza and the increased availability of far flung digitized collection items at the Huntington Library and National Gallery of Art have served to reestablish the significance of his work in the Hudson Valley in the years prior to his death. An authoritative transcribed version of his Journal was also published by Cornell University Press in 2010.

The engraver of the Plan of Esperanza was Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin, a friend of Peter DeLabigarre (the third French émigré of this tale) who is most celebrated for his portraits. Acquainted with the upper crust of New York society, Saint-Mémin was able to produce engraved portraits of dozens of prominent citizens and acquaintances as well as portraits from life of several of the Founding Fathers. His friendship with and early patronage by John R. Livingston makes Saint-Mémin’s participation in the creation of the Plan of Esperanza no small coincidence, as Livingston was one of the principal stakeholders in the venture. Whether the high-born Esperanza speculators retained Pharoux and Saint-Mémin individually or jointly is unknown, but Pharoux’s journal includes mention of passing along drawings so that Saint-Mémin could produce an unknown number of copies which today are cherished rare collectibles. It is possible Pharoux’s drawings are the same ones which which are now available as digitized manuscripts through the Huntington Library, though this is unclear.

Peter DeLabigarre is the fascinating figure who completes this émigré trio. Alf Evers spends an entire chapter of his book The Catskills on him — specifically the ventures DeLabigarre undertook in the Catskill Mountains for the benefit of science, mankind, and personal finances. Those ventures, done under the auspices of his friend and neighbor Chancellor Robert Livingston, included the notable and likely first recorded ascents of Overlook Mountain and Kaaterskill High Peak. DeLabigarre even named the latter “Liberty Cap” in his reports to celebrate America and France’s kindred Revolutionary spirit. DeLabigarre also famously tried to promote the cultivation of silk worms on the Livingston’s estates and was also a close friend to Edward, youngest brother of Chancellor Livingston and another member of the group of speculators at Esperanza.

Pierre DeLabigarre’s so called “Liberty Cap” at left of range above Kaaterskill Clove. DeLabigarre made what is probably the first recorded ascent of today’s High Peak on an expedition in the 1790s. He would have been able to view the mountain from his accommodations in Tivoli on the east bank of the Hudson. Palmer Photo, 2021.

Among DeLabigarre’s other ventures was the creation of a proposed town on the banks of the Hudson to be crowned by his estate “Chateau de Tivoli” and lying nearby the lands of Chancellor Livingston at Clermont. While his proposal for the town never panned out, the Tivoli of today is still known by the classical name granted to it by its famous émigré resident. The only other remnants of DeLabigarre’s Tivoli dream endure in an engraved map made by none other than Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin, and it is unknown if the actual survey work was conducted by DeLabigarre or by Pharoux as a talented mutual acquaintance. As the plans of Esperanza and Tivoli were being produced at virtually the same time and by people in the same circles it would be unusual if Pharoux wasn’t involved with both.

It is thanks largely to the research and digitization efforts of several major repositories and an auction house that the identities of the creators of the Plan of Esperanza are now definitively known. As such, this information certainly serves to contextualize certain aspects of the Plan of Esperanza which were of obvious interest even in the 1880s to William Pelletreau. In the 1884 History of Greene County he makes note of the inclusion of streets named Liberty and Equality, a facet of the map now demystified with the revelation that its creators were men endeared to the democratic principals of the French Revolution but not the violence that defined much of the 1790s which precipitated their removal to the United States.

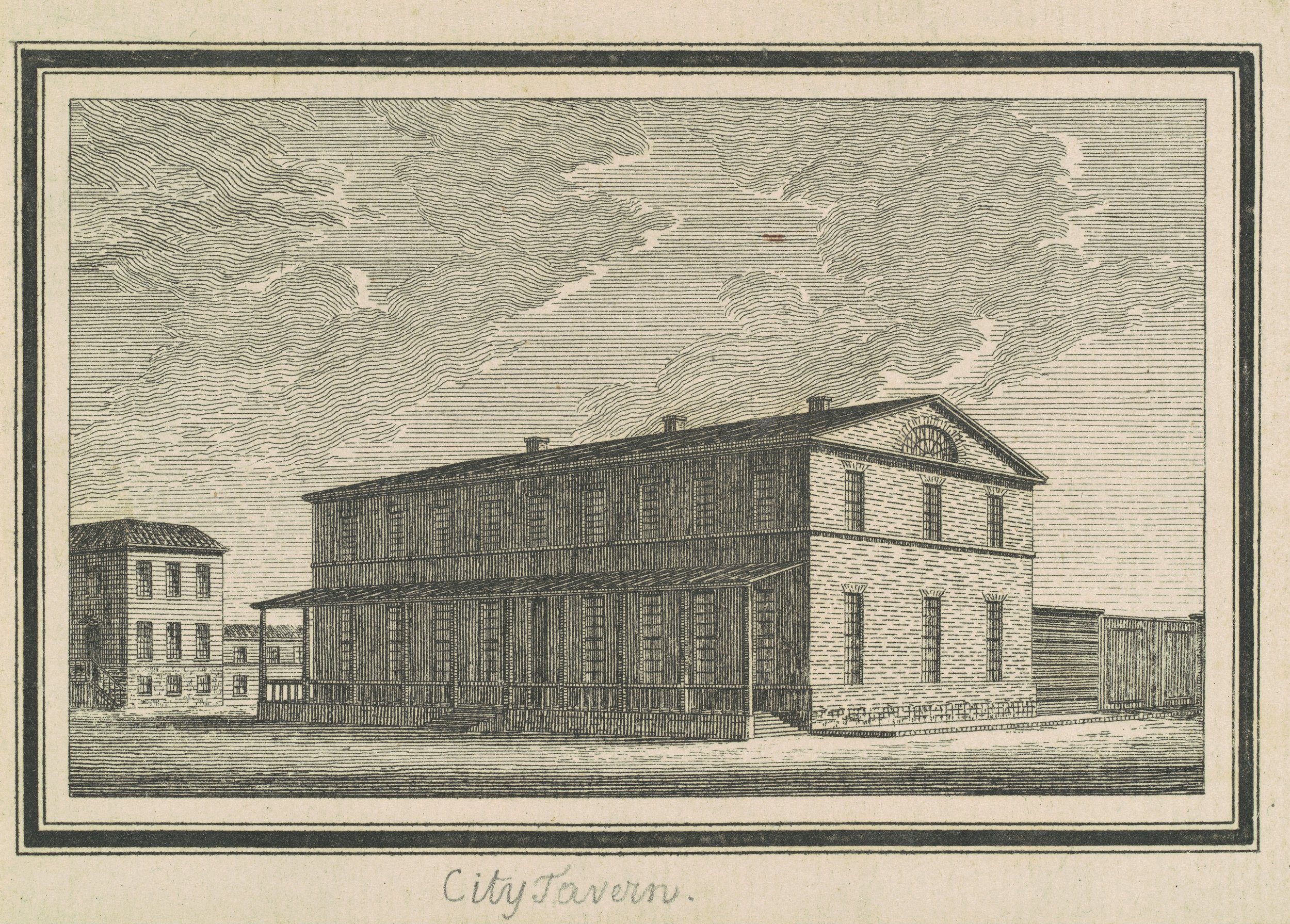

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Pharoux’s Plan of Esperanza is the part of the plan William Pelletreau didn’t know existed when he wrote his history in the 1880s. Not only did Pharoux prepare a map as surveyor, he also applied his visionary concepts of architecture and civic planning in a selection of drawings which were also engraved by Saint-Mémin to accompany the map. Saint-Mémin’s engravings of those buildings are now digitized and available online through the National Gallery of Art, and as a collection testify to a comprehensive vision for Esperanza which until recently has never been fully grasped by local historians. The scale and vision of the plan, coupled with an understanding of the background of the remarkable people involved, leaves more questions than answers as to why Esperanza failed. By 1801 portions of the proposed but unrealized City of Esperanza would be subsumed in a competing speculation led by Isaac Northrup and several businessmen from Hudson, resulting in the highly successful incorporation of the Village of Athens in 1805 as Greene County’s first fully realized planned community.

Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin, Esperanza Church, 1795. National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran).

Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin, Esperanza Market, 1795. National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran).

Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin, Esperanza City Tavern, 1795. National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran).

The Three Images above were all engraved by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin as part of his efforts to prepare enticing promotional material in partnership with Pierre Pharoux for their patrons who were developing a planned community on the banks of the Hudson at modern Athens, New York. These buildings, (which were never realized) offered potential investors a glimpse of the beautiful opportunity offered by the latest trends joining modern architecture with urban planning - in essence realizing the ideals of the new American republic in brick and mortar.

Questions and comments can be directed to Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian, via archivist@gchistory.org