The Irish Colleens of Saint Joseph’s Chapel

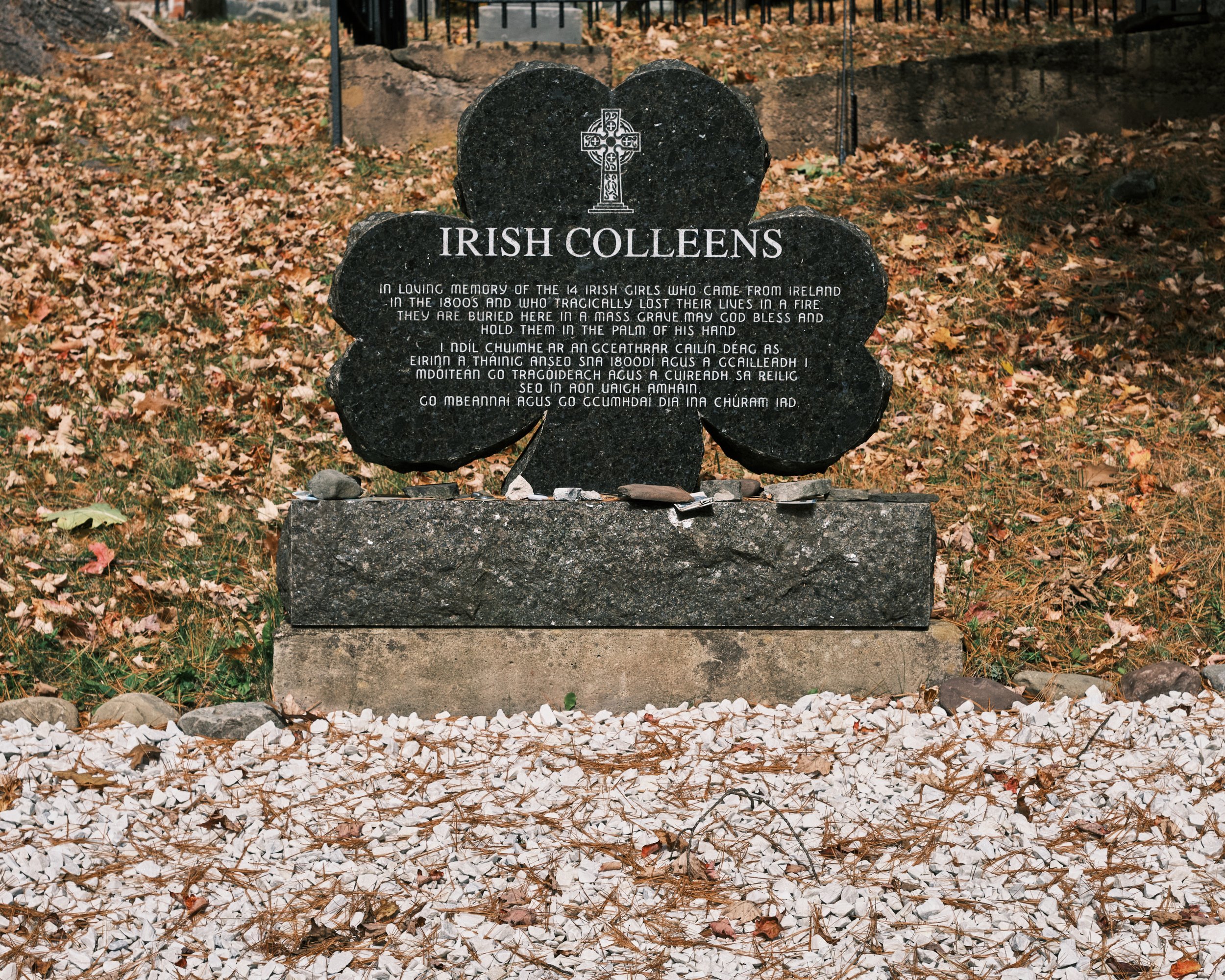

Near the Ashland/Prattsville Town Line overlooking the valley of the Batavia Kill stands a small chapel and churchyard on a rise above State Route 23. Passersby generally pay no heed to it as they travel past at sixty miles an hour, but for those who catch the sign “Oldest Catholic Church in the Catskills” and take time to stop the rewards are manifold. Saint Joseph’s chapel claims to have been built around 1800 during the earliest years of the settlement of Old Windham, and one might believe it to see the full churchyard with gravestones edging right up to the building’s walls. One stone in particular stands out — a granite shamrock upon which is carved the following:

Irish Colleens

In loving memory of the 14 Irish girls who came from Ireland in the 1800s

and who tragically lost their lives in a fire. They are buried here in a mass grave.

May God bless them and hold them in the palm of his hand.

The passage is repeated in Irish directly below. The humbling spectacle of the oldest Catholic Church in the Catskills paired with this marker near its entrance would create a particularly poetic and stirring composition were it not for some inconvenient details… Saint Joseph’s is not the oldest Catholic church in the Catskills, and the tragedy of the fourteen Irish Colleens never happened.

The granite monument to the fourteen Irish Colleens which stands near the entrance to Saint Joseph’s chapel and cemetery in Ashland, New York. Palmer Photo.

The marker to the Irish Colleens of Ashland is responsible for fomenting at least one or two inquiries annually by phone and email to the Greene County Historical Society. The story also invariably gets recycled now and again on social media. Countless people have offered speculation and possible avenues of research to uncover more details about this tragic yet vaguely contextualized disaster, but none have borne fruit and no local historian has ever found a lead. Thus, in order to finally put this myth to bed we must first consider the facts surrounding the industrialization of the Northern Catskills, the development of the Irish immigrant community in Prattsville and Ashland, and the origins of Saint Joseph’s Chapel itself.

The story of the arrival of formal Catholic services in Greene County is tied hand in hand with the creation of the great tanneries of Hunter and Prattsville in the second and third decades of the nineteenth century. William Edwards’ New York Tannery at Hunter village is widely considered to be the great pioneer of that industry and was put in operation in 1817 with backing from investors in New York City. The New York Tannery and others like it created a considerable demand for labor in the tanneries themselves and in adjacent trades. With every tannery that opened so followed a legion of tanners, carpenters, blacksmiths, drovers, bark-peelers, mechanics and the like — all added to the growing tally of skilled and unskilled labor rapidly filling the Northern Catskills.

At Hunter as early as 1830 it is claimed there was a large enough immigrant Irish Catholic contingent among the laborers there to merit the occasional visit of a Priest from Albany, which was then part of the New York Diocese. By 1839 those congregants were so numerous that a subscription was raised to secure funds for the construction of a church. This culminated in the completion of Saint Mary of the Mountain as the first Catholic Church in Greene County with Rev. Bernard O’Farrell as pastor the following Spring. Two years later in 1842, following the appointment of Rev. Michael Gilbride as the second pastor at Saint Mary’s, work was begun to create a mission chapel to service the growing Catholic contingent at Red Falls — a small hamlet east of Prattsville village along the Batavia Kill.

The Metropolitan Catholic Almanac first lists a church at Scienceville (the old name for Ashland) on the directory of Catholic houses of worship in the New York Diocese in 1843. The church at Hunter had been listed previously beginning in 1840, making Saint Mary of the Mountain the oldest Catholic Church in Greene County and Saint Joseph’s Chapel a close second. With the demolition of Saint Mary’s in 2017 the chapel at Ashland can now safely claim oldest surviving Catholic church in the County, though by no stretch of the imagination could it ever be dated to “circa 1800” — eight years before the Diocese of New York was even formed.

The need for a church at Red Falls was precipitated by the same type of development that had fomented the rise of an Irish Catholic community at Hunter. The vast tannery of Zadock Pratt at Prattsville (established in 1825) and one run by Foster Morss and his son Burton (established in 1830) at Red Falls were catalysts for the development of those communities, but they soon became just one part of the rapidly evolving industrial landscape in that section of the mountains during the Antebellum period. By 1850 Prattsville and the newly formed town of Ashland sported a cotton mill and two hat factories in addition to a number of lumber and grist mills, a developing cottage dairy industry, and the old established forest industries.

It should be said before we continue that the most important piece of evidence that the Irish Colleens tragedy never occurred is the fact that it was never recorded, reported, or recollected by anyone in the time since the event could have transpired. Fourteen women dying in a fire would be the second greatest disaster behind the Twilight Inn fire to have ever occurred in the County’s history, not to mention being the greatest industrial disaster to ever occur here. Such things do not get omitted from collective memory, nor were such stories overlooked by newspapers.

Disasters such as the one alluded to by the Irish Colleens monument were the catnip of newspaper editors in the 19th century. Editors reported every disaster to befall their respective communities - be it housewives catching fire while tending the stove, children drowning, uninsured warehouses burning down, or people dying of hydrophobia - and if such disasters weren’t befalling their readership then editors simply copied disaster news from other papers around the country. The reason for this was of course because at the end of the day disasters sold papers. People would have gobbled up the tale of fourteen immolated Irish women in the Catskills. No such disaster can be located in any newspaper database, and no mill or tannery in that area ever burned with the loss of any woman’s life.

It is important in supplement to this glaring lack of evidence to establish whether a scenario ever could have existed in which fourteen Irish immigrant women could have been killed in a fire - be it in a mill, boarding house, or otherwise. This analysis begins with the 1850 United States Census, being the census immediately following the height of the Potato Famine (when the Irish immigrant population should have been proportionately high) and subsequent to the 1848 opening of Burton Morss’ cotton mill at Red Falls. The 1850 Census is also the first in which every member of a household is listed with their place of birth.

What that census illustrates broadly is the following: a little over 6% of the population of Prattsville claimed to be Irish immigrants (≈125 persons out of 1,989 people), while a little over 2% of Ashland’s population (≈29 of 1,290 people) listed Ireland as their place of birth. Of those people, the Irish immigrants were predominantly members of family groups in which one or both of the parents were immigrants whose children were mostly or exclusively born in the United States. Irish immigrants not living in a family setting were predominantly unattached men working in industry or household servants and boarders generally numbering no more than one or two persons in the homes of established local families. One home in Ashland contained six immigrant Irish men with no clear trade specified living with Solomon Christian, a local farmer with a young family.

The entry from page 18 of the enumeration of Ashland, Greene County, from the 1850 United States Census showing Solomon Christian, his young family, and a slew of boarders who were predominantly male Irish immigrants.

The 1855 New York State census illustrates some interesting changes. Roughly 5.2% of Prattsville’s population reported their birthplace as Ireland (≈84 of 1588), while just under 2% of Ashland does the same (≈20 of 1094). This decrease, particularly in the Town of Prattsville, may have been due to the closure of some local tanneries and the transformation of the economic landscape of the town. Broadly the same fact remains constant however that most Irish immigrants lived within family units or were otherwise unattached males living as boarders. Several more unattached young women or daughters of families living elsewhere in town are listed working as servants with established local families.

The 1855 census interestingly also lists a Roman Catholic church at Ashland with an attendance of about 150 congregants — this number is roughly equivalent to the total number of Irish-American families living between Prattsville and Ashland who could have been potential congregants. This assumes for example that the fifty or so children appearing in households where at least one parent was an Irish immigrant in Prattsville would make up a portion of those attending while also not accounting for those practicing Catholicism who were not Irish-American.

The next census examined was the 1865 New York State Census following the Civil War. In this census surprisingly only 2% of the population of Prattsville reported their birthplace as Ireland, and in Ashland eight people stated they were Irish immigrants. These decreases correspond with a continuing decrease in the total populations of each town. Notably the Roman Catholic church is not listed as an active congregation at this time, though it reappears in later censuses. As with previous years those born in Ireland are almost exclusively part of family groups or servants in households of established local families.

The 1870 United States Census, 1875 New York Census, and 1880 United States Census all continue to illustrate this trend of general decline in percentages of the population of Prattsville and Ashland who reported their birthplace as Ireland. By 1880 nobody reports their birthplace as Ireland in either town. Though this may reflect minor reporting or recording biases it nonetheless illustrates how rapidly the initial Irish-American community associated with Saint Joseph’s appears and then disappears.

Cumulatively, these censuses illustrate that it would have been highly irregular in the years following the organization of Saint Joseph’s Chapel for fourteen immigrant Irish women to have found themselves in a scenario where they all could have died in a fire. While an event at a workplace would certainly be most likely, any fire that could have occurred would have killed more people than exclusively Irish immigrants. Take for example Burton Morss’ cotton mill, which was the largest employer at Red Falls, with a claimed figure of forty women and thirty men employed while it operated between 1848 and 1881. It is evident from the 1850, 1855, and 1865 censuses that the mill employed both men and women, and that many people from established local families worked alongside those who had been born elsewhere. Likewise, boarding houses in the area seemed to have catered to both men and women and boarders didn’t hail exclusively from one region or place of birth.

❈ ❈ ❈

While this is all quite interesting it should come as no surprise that all evidence stands in contrast to the tale related on the Irish Colleens monument. In fact the only surprise here seems to be the monument itself, which so far as can be discerned appeared along the staircase to the chapel sometime in the 1990s. An inquiry submitted by a researcher to the Greene County Historical Society in 2009 notes the appearance of the marker “about ten or fifteen years ago” and relates his desire to confirm the circumstances it commemorates. The marker pairs odd specifics (fourteen women) with useless dates (“the 1800s”) and omits where the disaster happened, only that there was a fire. Frankly the monument reads more like the end result of a children’s game of telephone… and that analogy may not be far from the truth of its origins.

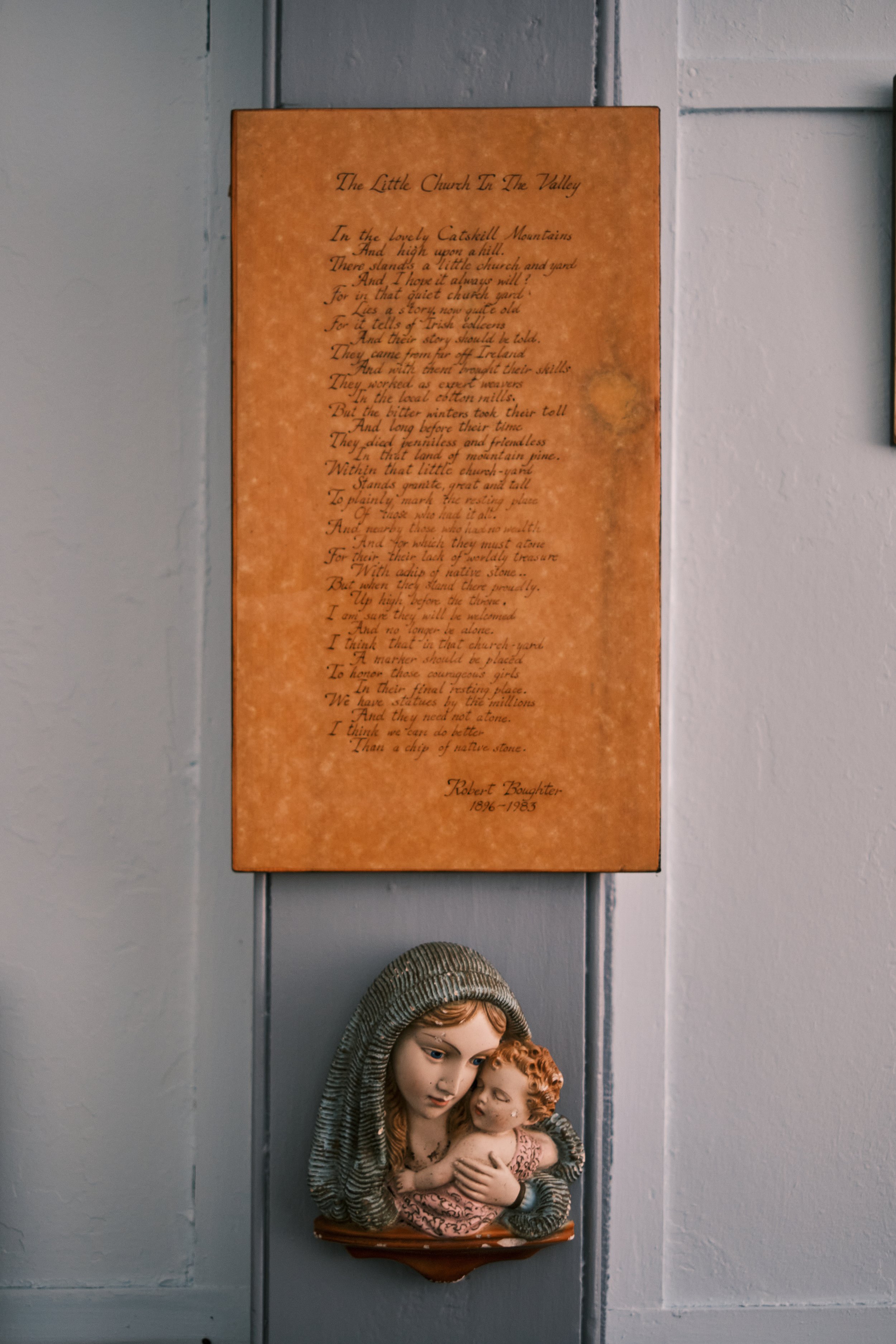

Robert Boughter’s poem “The Little Church in the Valley” displayed within Saint Joseph’s Chapel.

At some point probably in the 1950s or 1960s a poem was written by Robert Boughter of Windham lamenting the “haves and have nots” tale of the Irish immigrants who came to work in the mountains in the nineteenth century. His poem to the memory of the Irish Colleens, while not exemplary of the form, is a poignant and earnest tribute to the story Boughter understood to be the truth about the people who came to work in Red Falls at Burton Morss’ cotton mill. He paints a vision of the classic New England textile mill wherein floor upon floor of immigrant women and girls from the countryside toiled away in despair on behalf of fat cat bosses.

In Boughter’s poem those women die in anonymity after having lived a life of anonymity, being buried as he puts it “beneath chips of native stone” while nearby “stands granite great and tall to plainly mark the resting place of those who had it all.” He closes with an admonition to the reader that a marker should also be placed to commemorate those women, not alluding however to any disaster or mass grave. Boughter simply laments the tragedy of the scores of uninscribed fieldstones marking their burials, assuming without evidence that many represented the unattached “Irish Colleens” with neither family nor means to adorn their own graves. The mountains are loaded with cemeteries containing scores of unmarked headstones made from native fieldstone slabs, and it will take considerable further study to determine if this phenomenon is socioeconomic, an expression of piety, or some mixture of the two. Either way it was not a phenomenon unique to Saint Joseph’s or the Irish Catholic community in Red Falls.

Some of Robert Boughter’s aptly styled “chips of native stone” in the Catholic cemetery at Saint Joseph’s Chapel.

Boughter is of course imposing his own expectations on what the nature of the working community at Red Falls was during the mid-19th century and assuming that primarily imported labor comprised Burton Morss’ workforce. As said previously the censuses of 1850, 1855, and 1865 plainly illustrate this was not the case. Were Boughter’s vision of the past correct, this would have required nearly fifty percent of the Irish immigrant community in Ashland and Prattsville at its peak circa 1850 (roughly 150 people total) to be employed just at Morss’ mill, never mind all the other places those people listed as their actual occupations. Moreover, the cotton mill operated until 1881, well after the population reporting their birthplace as Ireland in both towns had dwindled to virtually zero. This all aside, it is important to remind everyone again that none of the mills there ever burned with catastrophic loss of life.

When Boughter died in 1983 he was laid to rest in the back of the cemetery at Saint Joseph’s among the “chips of native stone” he fancied as being the markers of the Irish Colleens. On his grave he had inscribed “The Irish Colleens” followed by his own epitaph “In Memory of Robert Boughter, 1896-1983.” In this way his own grave finally fulfilled the need he perceived for a marker to honor the women central to the story he contrived of the mill at Red Falls. This makes the subsequent appearance of the Irish Colleens monument not only somewhat redundant, but also illustrative of a progression in the evolution of an already somewhat imaginative vision of the past. Thus the Irish Colleens monument stands today an expression of misconstrued recollection rather than a long-overdue tribute to an actual tragedy.

History of course is merely our conversation with the available facts of the past. The discovery of new details can move that conversation in many directions, but the conversation only bears fruit if we act in concert with the evidence at hand. Perhaps it is time — out of respect to the legitimate story of the Irish Catholic community that once called this corner of the Catskills home — to finally put this legend to rest.

By Jonathan Palmer, Greene County Historian. Email Jon at archivist@gchistory.org

The interior of Saint Joseph’s Chapel, Ashland, New York. Palmer Photo.