Recalling Darker Days

In August of 1832 a foul and reeking sloop sat anchored off the shore at Athens filled with the dead and dying. A rowboat bearing litters plied between it and the shore, echoing Charon on the Styx as it continually returned empty of passengers. On shore, smoke billowed into the sky from burning buckets of tar as a lone horse and cart slowly made their way through the streets spreading lime in open gutters. The scene was apocalyptic, and all was at a standstill. Clergy and doctors had fled to the mountains out of base fear, and many of those who remained were soon laid low by the unseen foe. The wealthy and poor alike were not spared, and the greatest minds of the age were at a loss as to a recourse for the plague that had beset the region.

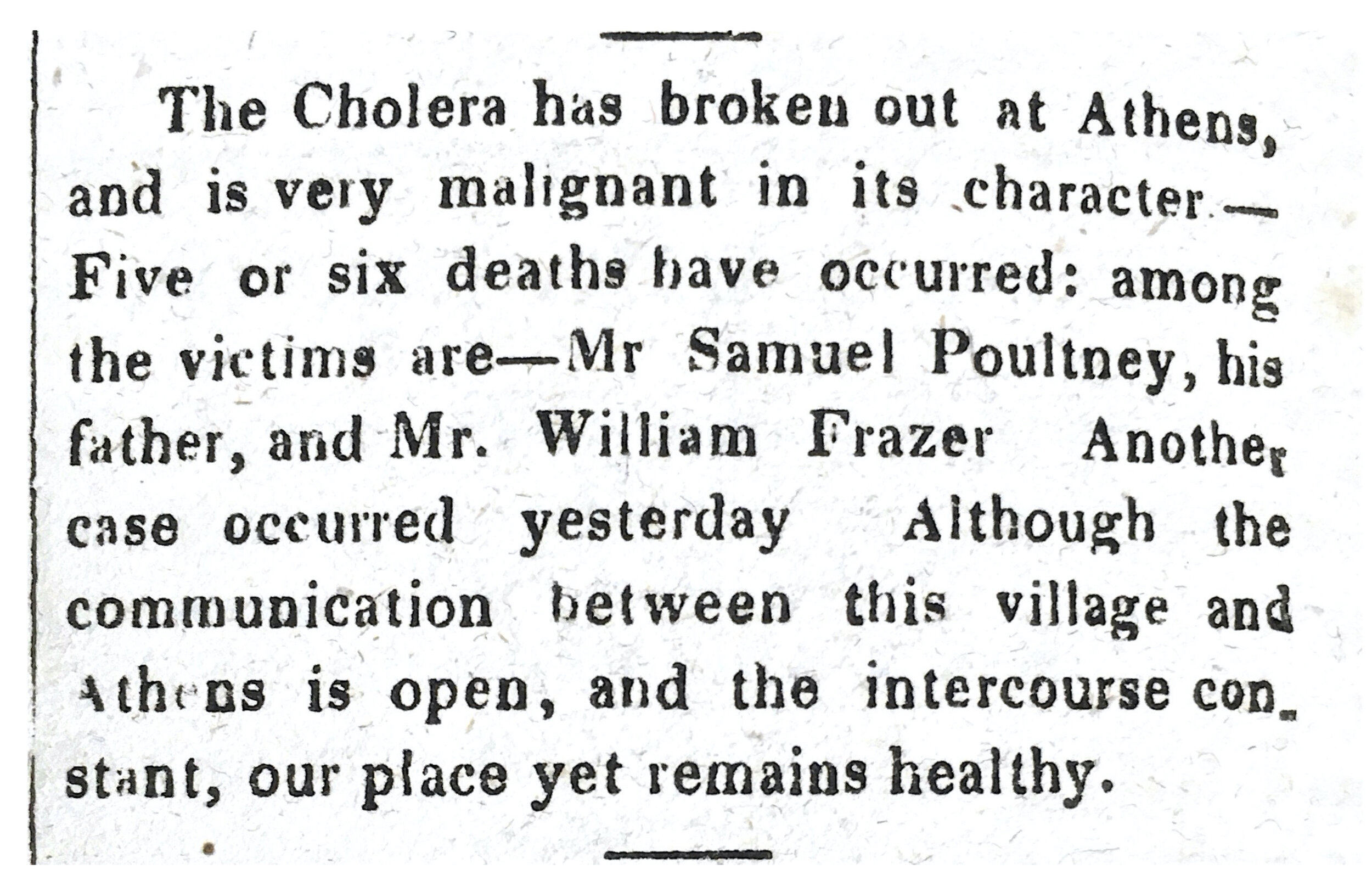

News from the Recorder on 16 August 1832.

The Cholera was a terrifying unknown, and across the County distinct Boards of Health all attempted as best they could to treat a disease they didn’t know the cause of. Extant receipts of the Boards of Health of Athens and Catskill testify to the dire nature of the situation and the town-wide mobilization that occurred in an attempt to stop the spread. At Athens James Foster’s sloop was rented as a temporary hospital at the onset of the epidemic in mid-August. His vessel was a well-used freight boat which had been laid up as river-borne commerce slowed drastically amid the fear that gripped the Valley from Albany to New York. The sloop, a poorly ventilated cargo vessel, was ill-suited to the role of a hospital. Between the sun beating upon its deck and the foul conditions prevalent in the hold it is a wonder any thought the vessel a suitable option for the care of Cholera victims. Mr. Foster netted the equivalent of three hundred dollars for its temporary use, also supplying material for litters as well as a wagon and workman for burying two victims.

A selection of other bills submitted to the Athens board of Health is as follows:

Nathan Clark hired out workmen from his Pottery on Market Street for part of a morning to dig a ditch as a sanitary measure.

Amos Durham, the cemetery sexton, was paid thirty eight dollars for the burial of the dead between August seventh and September twelfth.

Castle Seeley, the Village postmaster, submitted a bill for twenty eight dollars as compensation for several sizable orders of lime. He also sought reimbursement for money he personally paid Doctor Williams to attend the sick that August.

James Brown was paid three dollars total for his efforts crossing the river on several nights after the ferry stopped running to summon doctors from Hudson to attend patients at Athens.

Bill of Amos H. Durham, Cemetery Sexton, for services rendered the Athens Board of Health in August and September 1832.

~

Things were no better in Catskill by the end of August. Dr. Thomas O’Hara Croswell had been appointed the role of Health Officer by the newly formed Village Board of Health. He assumed that duty in addition to his responsibilities as postmaster, druggist, and physician, knowing there was probably no other person better suited to the task. He had been attending to the medical needs of Catskill’s citizens for practically forty years (his practice predated the County and Village governments by almost a decade) and he had seen much in that time. Recollections of the 1803 Yellow Fever probably tempered his natural optimism, reminding him of the not-infrequent futility of a doctor’s ministrations on the gravely afflicted.

Resolutions of the Board of Health of the Village of Catskill, 12 July 1832 edition of the Recorder.

Message to readers from Dr. Croswell in the 12 July 1832 edition of the Recorder.

Through July and into August he added statements in the Board of Health’s published reports, noting on several occasions “the village is unusually healthy at this time.” Readers of the Recorder probably found great comfort in his assurances, which were printed on the page opposite regional news where tabulations of the death toll at New York were updated weekly. In late August Catskill started getting cases, and notifications from the Board of Health, together with Dr. Croswell’s assuring words, ceased appearing altogether as the Health Officer became entirely consumed in his duties to the sick.

A lengthy bill tabulates the supplies requested in outfitting a temporary hospital which the Catskill Board of Health constructed for their Cholera victims. The shipping and warehouse firm of McKinstry and Day supplied everything from bread and milk to candles, matches, fabric for bedding, and even tar ostensibly for burning between August twenty-first and September nineteenth, finally receiving payment in November of that year. Likewise Solomon Woodruff put his wagon to use, carrying and spreading lime across the village for two months from July through August on credit, additionally carrying supplies to the Hospital when required.

It was all for naught, and most who contracted the Cholera that year succumbed to it. The village and town Boards of Health conducted all of their labors under the misguided supposition that the Cholera spread through “miasma” - odiferous and noxious fumes originating from the prevalent unsanitary conditions in their community. Inadvertently they ended up attempting to address some of the problems that indeed contribute to Cholera’s spread, but they never addressed fully the issues of groundwater and food that had been contaminated unknowingly by human feces. It would be another decade before fecal contamination of drinking water was known to be a cause of Cholera, and another fifty years before even the Village of Catskill had a municipal water system to offer its citizens safe drinking water.

All of this was naturally called to mind at the sight of the Hospital Ship USNS Comfort arriving this week in New York Harbor. How far a cry it is from the sloop anchored at Athens in 1832, and how far a cry from that epidemic are we as well. It is difficult for us even in the grips of this great crisis to fully understand the breadth and scale of the fear that our forebears endured at the onset of the Cholera, though we certainly have had a taste of it which the imagination runs with. The Cholera alighted itself on shores of the United States at a time when no scientific foundation existed to understand its root cause. Even the symptoms eluded the medicines of that age. It was not understood why or how the Cholera arrived, nor how its victims were selected, and diagnosis in that time was more often followed by death rather than treatment. It is a great triumph of our time that we know the disease we are fighting against, and the ammunition at our disposal to prevent its spread (however simple it may seem) has never been given a better opportunity than now to be effectively wielded. Further reading on the Cholera of 1832 is linked below.

USNS Comfort arriving in New York Harbor. US Navy via Getty Images.

Click here to read County Historian Ray Beecher’s article on the 1832 Cholera.

Click here to read Karla Flegel’s history of the 1832 Cholera in the Hudson Valley.

Click here to read about the Second Cholera Epidemic 1826-1837.

Click here to watch an interview with Dr. Fauci on the Daily Show concerning Covid-19.

By Jonathan Palmer, Assistant Greene County Historian