The Oldest Photograph of Catskill

In September of 2016 Barbara S. Rivette donated a curious photograph to the Vedder Library as a supplemental accession to her extensive collection. Mrs. Rivette hails originally from Catskill and is the daughter of Mabel Parker Smith, the late Greene County Historian who preceded Raymond Beecher. The photo Mrs. Rivette donated turned out to be an exceedingly curious artifact, and may prove to be one of the earliest surviving landscape photos of any location in Greene County.

Lets backtrack briefly to cover some previously trod ground. In 2018 an advertisement was found in a back issue of the Catskill Messenger from 1842 that announced the arrival of a photographer in Catskill. This traveling photographer stated he would be selling equipment and doing demonstrations of the Daguerrotype Process for the public at Van Bergen’s Hotel (probably in the vicinity of the modern Court House on Main Street). The Daguerreotype process was extremely new at that point, having been invented less than two years before as the first ever viable photographic technique. Daguerrotypes used polished metal treated with a chemical emulsion to literally burn a positive monochrome copy of the subject onto the treated plate for posterity. It was a time consuming process that required a studio setting to be properly executed. The photographer demonstrating this process in Catskill in 1842 was likely the first ever photographer to visit and ply his trade in this County, though he would soon be followed by a slew of local practitioners.

The Daguerrotype was refined over the ensuing decade before it was finally superseded by an alternative process: this being the somewhat more elegant Ambrotype. A variation of the wet collodion process, the Ambrotype had a shorter “day in the sun” and remained in common use only through the Civil War before being entirely replaced by the cheaper tintype. Using a treated emulsion on glass instead of silver, the Ambrotype was still a difficult process to take beyond the confines of the Studio setting because the delicate plate had to be exposed while the chemical emulsion was still wet. An exposed Ambrotype created what is more or less a positive image on a delicate sheet of glass, and the positive would then be mounted within a wood and velvet case for its protection. Naturally portraits make up the majority of compositions found on remaining examples of Ambrotypes, though an experienced photographer was capable of taking a landscape under the right circumstances.

Here is the Ambrotype donated by Mrs. Rivette:

The central building is the obvious subject of the photo, that building being an extremely early Ice House in the process of being filled by workmen. The most notable feature of the Ice House is the scaffolding structure across the front of it, which likely served the function of allowing workmen to slide blocks of ice along the length of the building once a conveyor belt hauled the blocks to the desired tier of the storage space. This type of design would become increasingly uncommon later in the 19th century. The other oddity on this building is the flag flying on it. The 28-star flag of the United States was official for only one year between 1846 and 1847 during the presidency of James Polk. It commemorated the addition of Texas to the Union and was quickly superseded following the admission of Iowa the following year. The fact that this flag is shown flying over the Ice House does little to help us date the image, as the Ambrotype process was not yet invented when this flag was the official US Flag in common use. It is far more likely that this scene dates between 1855 and 1860, and that the owner of the Ice House was flying an older flag which was too large to bother replacing right away.

Immediately to the right of the Ice House is the foundry of Benjamin Wiltse, which was established in 1808 and purchased by Benjamin Wiltse and his brother in 1839 when they moved to Catskill from Columbia County. This foundry produced cast metal goods of a primarily industrial nature and will hopefully be the subject of a later article. Fortunately for us this building also still stands virtually unchanged from its early 19th-century configuration and allows us to orient the photo almost exactly despite the passage of over 150 years.

Assisting us with the orientation of the photo are two of Catskill’s earliest brick blocks, one of which also still stands. These early brick blocks on Main Street date more or less to the 1820s, and the remaining one is the building which currently hosts an H&R Block on its lower end and the offices of the Management Advisory Group of New York at the upper end. Some of you might also recall this same old brick building as the home of DuBois’ Drug Store. That building is the one directly above the roofline of the Wiltse Foundry in the Ambrotype.

The figure below is an approximation of the position of the photographer based on the angle of the buildings and field of view. It is possible that the photographer was standing on the surface of the frozen Catskill Creek, but far more likely he was on the opposite shore (possibly even taking this photo from the lower floor of a building based on what is at “eye level” in the scene). Not knowing the focal length of the camera lens also makes determining their exact location difficult.

The most significant building in the photo, unfortunately out of focus, is the second iteration of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. This building, which stood on Church Street, replaced an episcopal church which had burned in 1839. A call was put out by the vestry in 1840 for design proposals for a new church to replace it, and Thomas Cole (a member of the design selection committee) was the creator of the winning proposal. Cole’s gothic church edifice was one of an exceedingly small number of architectural designs the artist ever realized in brick and mortar, though its exact appearance during his lifetime was never previously corroborated by any renditions or photographs other than Cole’s original design proposal.

To clarify: other photographs of this particular St. Luke’s Episcopal do exist from the 1890s, but all of them show what appears to be Cole’s original design with a tastefully added bell tower also in the Gothic style. What Cole’s original drawing tells us is that HE never intended a bell tower on the church. This put the photographic evidence at odds with the original plan. With the discovery of this Ambrotype we now have proof that for at least twenty years the second St. Luke’s appeared exactly as the artist had intended, and this is notable for helping to contextualize “Thomas Cole the aspiring architect” and “Thomas Cole the practicing architect.”

What became of all these buildings? To the best of our knowledge the structures in the background succumb to fire and demolition, as many of the residential homes do not seem to match current buildings in those neighborhoods. One of the old brick blocks was destroyed what must have only been a few years after this photo was taken and replaced by a block of reconstruction-era businesses of three and four stories in a more contemporary architectural style. The Ice House that made up the front and center of this photograph was long gone by the 1880s and replaced by a coal yard which apparently used the empty lot for storage. Whether that building burned or was removed will only be determined through further research.

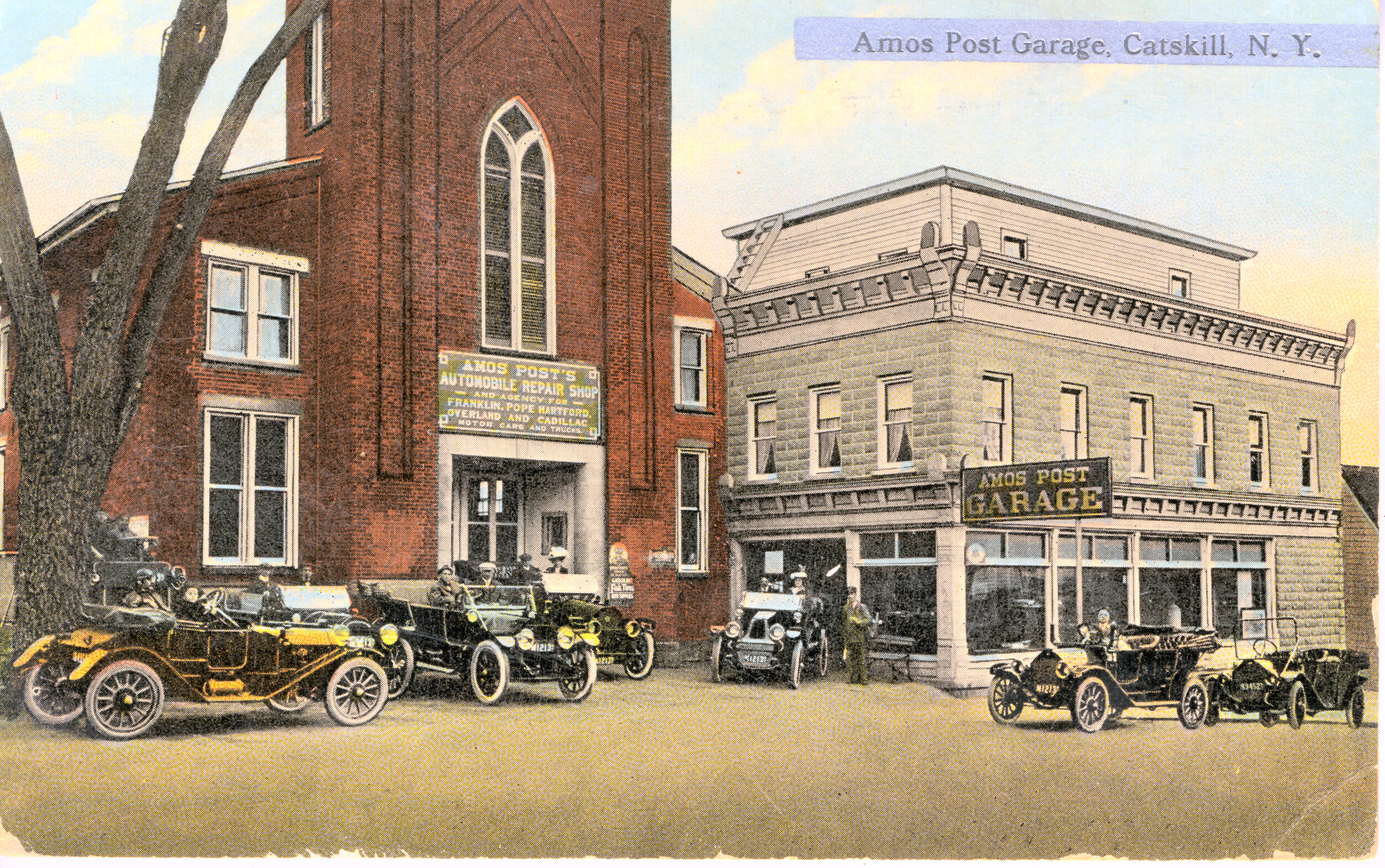

St. Lukes fell to the wrecking ball far more recently. In 1896 Cole’s church was abandoned and replaced by the third iteration of St. Luke’s Episcopal on the hill between Bridge and Williams Streets. Cole’s Church, suddenly empty, soon became the garage of Amos Post, changing hands a few more times before being utilized as the offices of the Daily Mail. When the new County government building was constructed Cole’s mostly forgotten 1841 gothic church was finally demolished to make way for a parking lot, and now “Church Street” is the only reminder we have of where this building once stood.

By Jonathan Palmer, Deputy Greene County Historian